Coordinating collective collections

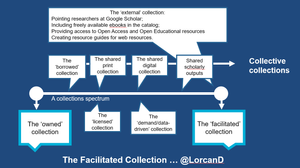

Collective collections are collections addressed at a level above the individual institution. I introduced our recent report on operationalizing collective collections in my last post, where I noted that there is a trend towards more managed collective collections, particularly within consortial settings. Collection coordination is central to building collective collections.

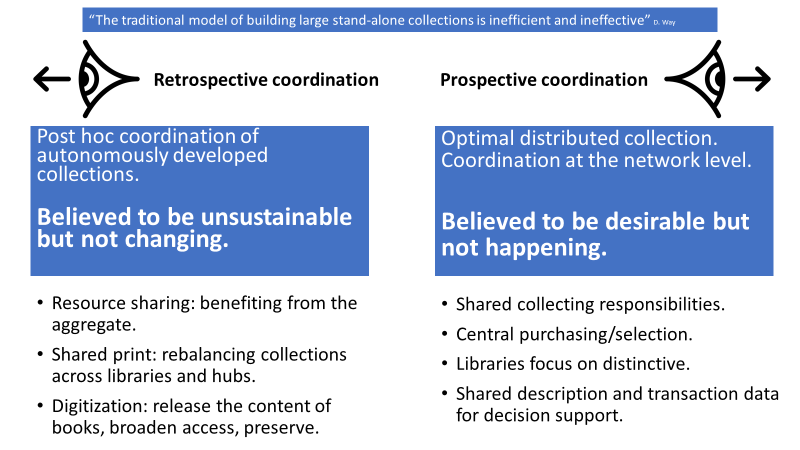

In the report we make an important distinction between two approaches to coordinating collective collections: retrospective collection coordination and prospective collection coordination. This is really about the level of coordination of collection development strategy and practice across a consortium or group. (I comment on our terminology choice at the end of this brief post.)

In the current model, collections are optimized locally and only retrospectively considered consortially.

Retrospective collection coordination

In the current model, collections are optimized locally and only retrospectively considered consortially. Shared approaches are layered over relatively autonomously developed collections. We can identify three important strands of retrospective collections activity, in each of which the BTAA has been active:

- Resource sharing: providing access to the resources of the full network to all members. Of course, resource sharing is evolving in interesting ways, becoming a channel for interacting with a variety of fulfilment networks, spot acquisitions, open access resources, and so on. One outcome of this is that we will see greater convergence between discovery, resource sharing, collection development and acquisitions. We can expect to see the links between these service areas become more automated and data driven. So, in a simple example, acquisition of articles or books may be triggered at some level of demand as indicated by discovery or resource sharing patterns of use.

- Shared print: coordinating stewardship of the print and scholarly record at the network level. This has been a major consortial interest in recent years. It is being coordinated by existing resource sharing networks, but new affiliations have also emerged to address shared print specifically, and we are seeing nascent collaboration across these.

- Digitization: selective digitization of collections. Digitization was given a boost by the Google initiative, and Hathi Trust has emerged as an important collaboration, consolidating access, management and preservation.

Shared print and resource sharing are alike aspects of collections logistics.

These areas have tended to be managed independently. There is great opportunity to coordinate them more strongly at the consortial level. Shared print and resource sharing are alike aspects of collections logistics, for example, thinking about optimal distribution of collections for rapid delivery across a consortium. ReCAP is particularly interesting in this regard, representing a hub which consolidates print collections, a logistical infrastructure, and stewardship responsibilities. And digitization could be driven by demand in context. This begins to move us towards a more prospective model.

Prospective collection coordination

A prospective collection coordination model offers stronger coordination of collecting activity across the network. This could be based on some division of collecting responsibilities and better awareness of systemwide distribution of collections, or even on a move of some decision-making and budget to the center (shared acquisition of e-books for example, or of open access collections). In this model, collecting activity could be optimized across the network rather than at the individual library level. An approach might be based on type of material, or publisher, or subject. Over time, addressing particular needs at a shared level might allow institutions to specialize in areas of local expertise or distinctive research interests. In this model shared print is not a retrospective rationalization of the collective collection, but a formative element of its development.

In this model shared print is not a retrospective rationalization of the collective collection, but a formative element of its development.

Of course, consortia are used to working with a version of this model for licensed materials, but it is not common for purchased or print materials.

While attractive in theory, prospective collection coordination has proved difficult in practice and is not widely adopted outside of some niche areas. There is some concern that coordination costs are high, potentially reducing local responsiveness (to particular faculty or learning needs), and there is reluctance to surrender local decision making or local control over budgets.

While there is some acceptance that the retrospective model of coordinating relatively autonomous collections model is inefficient, it has been easier to achieve in practice than a prospective model. This is because it does not require strong coordination of institutional collection strategies. It also seems that the risks of working with legacy collections are perceived to be less than those associated with prospective collection development, which will require a new level of mutual interdependence and ceding of control or budget.

In our discussions with BTAA and other librarians we sensed a real desire to make progress with a prospective coordination model, while acknowledging the difficulties.

Of course, the two are not mutually exclusive and if prospective collection coordination were to become more common it would exist in concert with the retrospective approaches we identify. More optimal distribution of collections would make the whole system more efficient.

A note on words

We found the use of ‘coordination’ and ‘prospective’/’retrospective’ useful in various ways.

In particular, “collaborative collection development” comes with a host of strong opinions and memories of less than successful outcomes.

Our use of coordination has two aspects. First, and more broadly, we discuss library consortial activity as involving various degrees of coordination along a spectrum from consolidation to relative autonomy. “Coordination” admits of some possible variability in approach. In particular we wanted to emphasise that the degree of coordination is a negotiated outcome – not a defined given. This is related to the second motivation. It is free of the legacy associations or preconceptions that “collection development” or “collaborative collection development” often inspire. In particular, “collaborative collection development” comes with a host of strong opinions and memories of less than successful outcomes. In summary, “Collection coordination” acknowledges a discretionary approach and is neutral in respect of past practice or expectations.

Our use of “retrospective” and “prospective” is influenced by Karla Strieb’s usage: “Shared Collections: Collaborative Stewardship, Chapter 1: Collaboration: The Master Key to Unlocking Twenty-First-Century Library Collections.”

Acknowledgements: This blog entry is based on the text of Operationalizing the Big Collective Collection by Lorcan Dempsey, Constance Malpas, and Mark Sandler.

Our thinking was influenced by a broad range of discussions with colleagues in BTAA libraries, in OCLC, and in other organizations with an interest in these topics. A full list of acknowledgements is included in the report.

Picture: I took the picture of the Wilson Library at the University of Minnesota.

Note: Cosmetic amendments on 31 March 2021 include addition of feature image, addition of headings and improved spacing.