I returned from my travels last night to find a new edition of the Atlantic waiting for me. It grabbed attention as it has been redesigned, and I liked the redesign. But also, my eye was caught by the title of Andrew Sullivan’s essay ‘Why I blog’.

Sullivan’s whole essay could be quoted, but as he notes, one of the advantages of the blog commentary is that you can provide a link. The reader can jump to the work being discussed.

He talks about the characteristics of the blogger’s activity ….

No columnist or reporter or novelist will have his minute shifts or constant small contradictions exposed as mercilessly as a blogger’s are. A columnist can ignore or duck a subject less noticeably than a blogger committing thoughts to pixels several times a day. A reporter can wait—must wait—until every source has confirmed. A novelist can spend months or years before committing words to the world. For bloggers, the deadline is always now. Blogging is therefore to writing what extreme sports are to athletics: more free-form, more accident-prone, less formal, more alive. It is, in many ways, writing out loud. [Why I Blog – The Atlantic (November 2008)]

…. and emphasizes its evolving place in a richer ecology.

In fact, for all the intense gloom surrounding the news-paper and magazine business, this is actually a golden era for journalism. The blogosphere has added a whole new idiom to the act of writing and has introduced an entirely new generation to nonfiction. It has enabled writers to write out loud in ways never seen or understood before. And yet it has exposed a hunger and need for traditional writing that, in the age of television’s dominance, had seemed on the wane. [Why I Blog – The Atlantic (November 2008)]

Sullivan looks to lofty precursors, Plato, Pascal, Karl Kraus, and, above all, Montaigne.

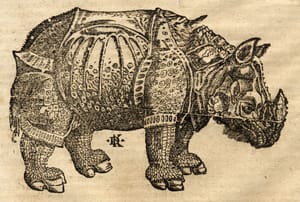

But perhaps the quintessential blogger avant la lettre was Montaigne. His essays were published in three major editions, each one longer and more complex than the previous. A passionate skeptic, Montaigne amended, added to, and amplified the essays for each edition, making them three-dimensional through time. In the best modern translations, each essay is annotated, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, by small letters (A, B, and C) for each major edition, helping the reader see how each rewrite added to or subverted, emphasized or ironized, the version before. Montaigne was living his skepticism, daring to show how a writer evolves, changes his mind, learns new things, shifts perspectives, grows older—and that this, far from being something that needs to be hidden behind a veneer of unchanging authority, can become a virtue, a new way of looking at the pretensions of authorship and text and truth. [Why I Blog – The Atlantic (November 2008)]

Coincidentally, I was returning from a trip to Cambridge University Library where we were privileged to be taken on a tour of their current Montaigne exhibition by Professor Philip Ford.

In 2008 Cambridge University Library received the Montaigne Library of Gilbert de Botton (1935–2000), a remarkable collection of books connected with Montaigne, his life and times, and his library, including ten of Montaigne’s personal copies. This exhibition draws on the collection to celebrate a writer whose book has for more than four hundred years fascinated its readers with glimpses of the complex, subtle, shifting self it seeks to portray. [‘MY BOOKE AND MY SELFE’: MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE 1533–1592]

I particularly liked this quote …

In 1570 Montaigne resigned from the Parlement and went to Paris to publish La Boétie’s works. The following year, on his thirty-eighth birthday, he retired from public life. He spent most of his days in his library, a circular room on the third floor of a tower at the château, where he had inscribed on the rafters quotations from his favourite works. Around him were some thousand diverse volumes, of both ancient and modern writers. ‘There without order, without methode, and by piece-meales I turne-over and ransacke, now one booke and now another. Sometimes I muse and rave; and walking up and downe I endite and enregister these my humours, these my conceits’. It was here that the that the Essais took shape. [‘MY BOOKE AND MY SELFE’: MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE 1533–1592]

Musing and raving, humours and conceits: not a bad account of blogging.

Note: see commentary by John Naughton and Nick Carr.

Note: see the Worldcat Identities pages for Montaigne, Philip Ford, Kraus, Pascal and Plato.