When I think of the Google Books initiative now, three things stick with me. The first is simply what an audacious idea it was – to digitize all the books. The second is that without it, the book literature is less accessible than the web literature, which seems a pity. Google Books has allowed fine-grained discovery over the topics, people, places and so on which otherwise would largely be hidden between the covers.

The third is more subtle, but marks an interesting shift in how we think about library collections and books in general. Before the initiative, we thought of the books in library collections as a vast expanse. We could not see the edges. They were like an ocean. Afterwards, the aggregate library collection appeared more bounded, more finite. More like a reservoir which could be measured and managed. And as Google spoke with various libraries about filling out parts of their digital corpus this became clearer. Indeed, it made it more realistic to actually talk about an ‘aggregate library collection.’

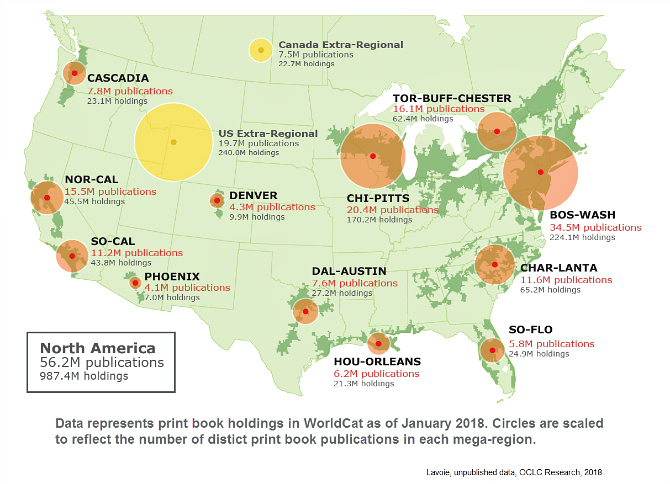

WorldCat represents the holdings of thousands of libraries around the world. It is the best available proxy for the aggregate library collection and by extension for the scholarly and cultural record of which libraries are the steward.

The empirical basis

OCLC and WorldCat have played an important role in this shift also. WorldCat represents the holdings of thousands of libraries around the world. It is the best available proxy for the aggregate library collection and by extension for the scholarly and cultural record of which libraries are the steward. In recent years, we have looked at providing an empirical base for discussions about that aggregate collection. This has meant that we can talk about the aggregate library collection or the collective library collection while having a real sense of its contours, in whole or at different levels (the collections in a particular region, for example, or the intellectual output of a particular country). While much of work has been in North America, we have also done work with library collections elsewhere.

In fact, an important early analysis of this kind was of the original ‘Google 5’ libraries who participated in the ‘Google Print Library Project.’ The findings here have been confirmed over subsequent investigations, largely carried out by Constance Malpas and Brian Lavoie. Especially notable is the finding that, in my colleague Brian Lavoie’s words, rareness is common – many libraries do in fact have materials that are not widely held. Which in turn leads to the need to have wide library participation to ensure broad coverage of the published record (in resource sharing, digitization, or other initiatives).

Brian has just written about some of that work – mining WorldCat for insights about the aggregate library collection and the characteristics of the scholarly and cultural record it represents. He presents an updated version of a map of library collections in the US and Canada, originally created several years ago by our colleague J.D. Shipengrover for our Print management at mega-scale report. This shows the concentration of library collections laid out over Richard Florida’s mega-regions framework.

A reservoir of books

I think that this picture – and the variety of analyses that accompany it – has been influential in the shift I mentioned above – the shift to thinking about library collections as a reservoir. It puts a real shape on the distribution of the aggregate North American library collection, quantifies it, and hints at the type of regional discussion about shared management that we are now seeing.

Reading this piece by Brian Lavoie reminded me how much I love the map of potential “mega-scale libraries,” were we to combine our print holdings regionally. https://t.co/jBnKOfUmPr // pic.twitter.com/4lhbJ5JBRL // Dan Cohen (@dancohen) September 20, 2018

An important aspect of this more bounded view is the emergence of what I call collective collections – where collections are addressed at various aggregate levels above the individual institution.

A collective collection might be realized at different levels of integration: through data (a visualization, for example), or through discovery (what is available through a particular discovery interface), or through federating applications as in consortial borrowing (what is available for lending), or through actual physical consolidation (at CRL, CAVAL, ReCAP, or some other shared storage), or through some other agreement. A collective collection might also be at different geographic scales: state, regional, national and so on.

Observations on collective collections

Here are some brief observations about collective collections, in terms of how they are managed and in terms of implications for their use.

- Visualising and analysing the collective collection: Where we have aggregate metadata or full-text from collective collections, we can visualize them in interesting ways, identify patterns in their composition, and draw out useful inferences touching on a range of issues. This might be about the management and disposition of collections (as in the mega-scale report mentioned above) or about the body of knowledge represented by those collections (as for example, in our study of the Irish published record, summarized here). Of particular interest in the latter case, is the recent announcement that the HathiTrust Research Center now “provides access to the text of the complete 16.7-million-item HathiTrust corpus for non-consumptive research, such as data mining and computational analysis, including items protected by copyright.“

- Operationalizing the collective collection: In recent years, the management of print library collections at the collective level has become an active area of discussion, planning and implementation. Existing organizations have taken this on as an activity (e.g BTAA) and some new organizations have emerged (e.g. WEST, EAST). Managing the collective collections of these groups has had a regional flavor, which makes sense from a logistics point of view.

Decisions about consolidating print collections are also influenced by the availability of digital surrogates. The Internet Archive and Google Books are important in this context. The role of HathiTrust is of special interest, given its mission to preserve the scholarly record and the fact that it is a collaboratively managed within the library community. The relationship between the digital resource curated by HathiTrust, the print resource curated by CRL, and the arrangements put in place by shared print collaborations will be more closely managed within an evolving ecosystem of services.

These activities are about retrospective collection development, configuring materials that have already been added to library collections. At the same time, the changing role of the book collection, the emergence of shared approaches to management, and the availability of new analytics services will make prospective, collaborative collection development more feasible than it has been in the past, as libraries do actually think about building and maintaining their collections in a collective context. - Calibrating the collective collection: WorldCat (and union catalogues in other parts of the world) have emerged as important sources of comparative intelligence as libraries begin to look at print collections in aggregate and think about managing particular collective collections. And also as libraries want to calibrate their collections against a regional, national or broader context. Or as they want to calibrate their collection against existing digitized collections. Or as they want to think about prospective collection development in collaboration with peers. Having intelligence about collections at various aggregate levels is now increasingly important, as libraries want to make responsible decisions within a regional group or in the context of general availability, and as groups want to make decisions about coverage and overlap.

Increasingly, libraries want to balance individual managing down of collections with a collective responsibility to the print scholarly and cultural record. And of course, different libraries and groups will recognise different responsibilities here. The ability to record retention commitments in WorldCat is an important infrastructural element, as libraries and groups can disclose important intelligence about their collections to help decision making.

Increasingly, libraries want to balance individual managing down of collections within a collective responsibility to the print scholarly and cultural record.

The management of collective collections also influence how libraries organize themselves and their services. Here are two areas of note in this context ….

- Collaboration at scale. Operationalising collective collections will happen inside consortial arrangements, existing, or as noted above, newly created. Much of this activity will have a regional scale, given the logistics of print materials. Although there is also a desire to aggregate or coordinate at higher levels and certainly there is advantage in having consistent policy frameworks. At some stage we might expect to see a level of coordination which assures the integrity of the print scholarly and cultural record.

At the same time, some activity may be better carried out at network scale. It is useful to have data at this level for example and OCLC supports a network of over 16000 libraries who collaborate at scale to describe, discover and share their collections. This has resulted in important infrastructure in WorldCat and associated services which is widely relied on. HathiTrust is in an interesting situation – will it evolve the organizational and sustainability models for it to become a persistent part of infrastructure, widely relied on in the library community and beyond? Will it scale to support library collaboration at network level?

In this way, the collective collection throws up questions about models and issues of collaboration at several levels. I have discussed many of these questions elsewhere. - Library logistics. Logistics is about moving materials quickly and efficiently through networks. Library operations increasingly have a logistics flavor – thinking about how best to manage stocks and flows. We will see increasing interaction between collection development, resource sharing, shared print and digitization as libraries look at an ecosystem of services around effective management and delivery of collections. This will be multiscalar (Ohio State participates in OhioLINK, BTAA and HathiTrust, for example). And it will involve interesting decisions about consolidation vs federation (of collections, data and applications), which in turn involves various tradeoffs, notably between efficiency and control at different levels (what sort of authority, for example, will individual libraries cede to consortia of which they are a part).

Libraries have entered a phase where they are now looking at managing print collections as a finite resource, and where there is systemwide attention to collective collections. Collections are reservoirs to be managed. We are in a period of organizational design and innovation as new frameworks for thinking about and managing collective collections are put in place.

Libraries have entered a phase where they are now looking at managing print collections as a finite resource, and where there is systemwide attention to collective collections.

Thanks to my colleague Brian Lavoie for comments on an earlier version of this post.

Related entries:

- Systemic change: CIC and Google

- The anatomy of an aggregate collection (a discussion of the original Google 5 analysis).

Picture: I took the feature picture at the Hoover Dam and Reservoir, Ohio.

Note: Cosmetically amended on 27 March 2021 to add headings and feature picture. Summary sentence and pullquotes added 8 November 2022.