I have been glancing through the contributions to

HANSON, T. (2005). Managing academic support services in universities: the convergence experience. London, Facet.

They examine convergence between libraries, IT and other support services in universities. This is a phenomenon more common in the UK than elsewhere: more than half of UK universities have adopted some form of converged model according to the editor. The contributions are mostly written by central actors in planning or managing converged services in the UK, alongside a historical perspective, and brief summary articles on the rest of Europe (based on a survey by Mel Collier), the US and Australia. Included also are some discussions of why a converged model was not adopted.

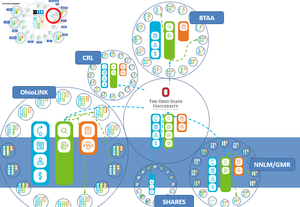

There is a variety of patterns of convergence, and it is very clear that local personalities and politics are decisive. Common is some coming together of the library and the campus computing or IT services, but other units may also be drawn in: management information systems, e-learning developments, language labs, audio-visual support and so on. I have wondered in these pages whether the founding type of library/IT convergence that is central here is an artifact of an earlier time and queried whether …

… it now makes more sense to associate the library with emerging support for e-learning and e-research, creating a set of capacities aligned around academic systems and services, and the management of research and learning data. [Lorcan Dempsey’s weblog]

(Indeed, in their review of Australian developments, Helen Hayes and Vic Elliot note a more recent trend to convergence between library and online learning services. p.176)

That said, what comes across in many of the discussions here is the importance of scale and of the ability to more flexibly re-allocate resources and make connections in a bigger unit. Conversely, some contributors point to the dangers of a converged service appearing too big – attracting 5-10% of the overall university budget according to Nigel Macartney – and presenting an attractive target for cuts. Apparent also, at least some of the time, are potential benefits in consolidation of both infrastructure and ‘customer’ relationship management. An interesting occasional theme is the additional institutional political influence the Director of a converged service may have. However, a couple of contributors also express concern that the breadth of expertise and attention required to effectively manage a wide range of services is such that some areas may inevitably be less well addressed. And specific to the UK is the common mention of several national policy documents and initiatives which encouraged this direction in the nineties.

I imagine that Derek Law’s comment in his contribution might be applied to several of the others here: “This author has noted elsewhere the tendency for institutions to (re)write their history in terms of principled and timely decision-making, rather then the somewhat grimmer pragmatic institutional politics which in reality usually drives change”. (p.97)

Anyway, skimming the articles here, my eye was caught by several passages …

Paradoxically, although convergence began in the USA, it has been proportionately more pervasive in the UK. (Clive D. Field, p 10)

Staff development and communication policies, considered to be important to bring about cultural change, were developed but with too much emphasis on ‘process’ and not enough on actual delivery of success in getting staff to take ownership of what had emerged. There was no ‘mourning’ of the passing of some of the old cultural icons that were swept away with convergence or celebration of new things that emerged. (Michele Shoebridge. p. 32)

… Information Services is still perceived in the University, and largely also in the division itself, as the Library Service and the Computing Service with new and confusing names. (Cathryn Gallacher. p.52)

We believe that true convergence requires an acceptance of common professional values, including evidence-based and reflective practice. (Margaret Haines et al. p.74)

At the time Information Services was created its budget and staff numbers was broadly equivalent to each of the then faculties and was not perceived as a problem. However, once the organization moved to eight schools, each of which had much smaller budgets, and the Registrar’s area was broken up on the administration side, the Information Services budget became the exception rather than the rule. It had the largest budget and staff, and began to be questioned on those grounds, rather being judged merely on cost effective service provision. (Sue Clegg. p.85)

The characteristics required in the head of the converged service depend to a large extent on what is expected of the convergence – if there are major structural problems to be overcome then tenacity, political savoir-faire and HR skills will be more important than than the technical understanding which might be needed if the structure and people are right but the IT strategy is defective. ….. The will to work together and not to be precious about tradition or territory is more important than any formal structure. (Tom Crawshaw. p.113)

Probably the most effective local influence on convergence at Swansea has been the simple expedient of combining library and computing services and staff in a single building. (Christopher West. p.120)

Ultimately it is people – not structures – who deliver services and working together depends more on creating the right climate than finding the best design. (Sheila Corrall. p.151)

World-class institutions do not have converged service delivery; there could be considerable debate over the names in the top 100 worldwide and their ranking, but it is the case that these institutions have no evident converged approaches to service delivery. (Mark Clark. p.157)

Some of the newer and smaller universities seem to be able to adapt to changing needs as they occur whereas such flexibility often proves more difficult in larger and older institutions. It is also true that structural change, at least in the Australian higher education sector, has often been driven by strong personalities and power plays during a time of constant change in which responsibilities have been reviewed and redefined to meet new challenges. (Hayes and Elliott. p.177)

Our hypothesis is that conditions in Europe [outside the UK] are generally not conducive to convergence. Such conditions could include: powerful decentralized administrations, conservative policies, and the level of maturity or professionalization of university services. (Mel Collier. p.199)

As one library director I interviewed succinctly put it, ‘The only thing I discovered is that structure does not mean a tinker’s damn. If people have a good attitude and can communicate, structure does not matter.’ (Larry Hardesty. p.210)