Introduction: boundaries between reading, interaction and workflow are blurring

It is useful to think about AI as a new cultural technology, a phrase development psychologist Alison Gopnik has been using.

Instead, these AI systems are what we might call cultural technologies, like writing, print, libraries, internet search engines or even language itself. They are new techniques for passing on information from one group of people to another. Asking whether GPT-3 or LaMDA is intelligent or knows about the world is like asking whether the University of California’s library is intelligent or whether a Google search “knows” the answer to your questions. But cultural technologies can be extremely powerful—for good or ill. // Alison Gopnik

Thinking in this way broadens the context of the library discussion about AI. A new cultural technology will ramify through the ways in which we create, curate, interact with, and communicate knowledge artifacts. This has implications for social trust and confidence, for the boundaries between content, interaction and workflow, and for what we value and transmit in the scholarly and cultural record.

This general use also makes it very important for libraries to advocate for transparency and good practices in the training collections for the Large Language Models (LLMs) used in these services. They need to be informed consumers, and reflect on how to use their collective influence. It is important to understand how such models are constructed, and the potential for bias and partiality given the dominant and sometimes harmful perspectives represented in the historical record they are trained on. It is also important to gain practical experience of how such services behave, how they are not like search engines, for example.

We can already see incremental changes in how we interact with informational resources. A set of services is becoming more common in daily tools.

For example, the search/summarise/sources pattern is becoming familiar from search services which deploy Retrieval-Augmented Generation models. See Microsoft CoPilot, Perplexity, or the new search feature in ChatGPT, for example, as well as the growing range of more specialist scholarly or research resources (see Scholarcy or Undermind, for example). Library and scholarly service providers are also carefully moving in this direction (see for example Clarivate or Digital Science).

There is an overlapping set of services that allows you to manage a collection of documents or other resources, and to interact with them in various ways. Such 'research assistant' or collection management services offer a suite of services. NotebookLM from Google, for example, has been much in the news recently, in particular for its ability to re-present submitted materials in the form of a very life-like podcast. Beyond this media-friendly feature, it supports other ways of interacting with a group of resources, summarization for example, or question-asking.

One common feature of these services is the ability to 'ask a PDF a question.' There are also multiple general purpose 'document chat tools' where this may be the primary focus.

Increasingly, I find that it is quite useful to be able to ask a document questions in this way - especially where it sits within existing workflows, in the browser, in my reference manager, when a PDF opens in Acrobat, and so on. It is useful to summarize, to look for stuff, to remind myself of a passage, to work with long documents. This is not necessarily a substitute for reading, when I do indeed need or want to read something. However, it is a way of navigating, prospecting, or locating, and can accelerate discovery.

Given I found myself doing this more, I thought I would have a closer look and quickly ask several services the same question to see whether there was much variation in response or whether one or the other was more helpful from my point of view.

The services I look at are Microsoft Copilot, Readcube Papers from Digital Science, Adobe Acrobat, Google's NotebookLM, ChatGPT, and Scholarcy.

So my focus here is very specific. This is a quick exploration driven by curiosity. It is not a carefully controlled experiment or research investigation. This is especially the case given the variety of ways in which the services differ, the probabilistic way in which the LLMs work, and the different environments in which the services are embedded. While my central theme is looking at question-asking across several services, I will certainly discuss these broader questions, but in an anecdotal way.

In particular, it should be noted that the same question will potentially produce different responses when re-run against an LLM. I was very aware of this when looking at the outputs from the various services, and for this reason I reran the question against the services after an interval of a day. For the purposes of comparison I include this second round of outputs below, although I do not analyze them closely.

This post is structured as follows.

- Asking documents questions: reflections on a simple example I introduce a question and note some context.

- Looking at the outputs I look at the responses to my question, and explore some characteristics of particular services.

- Reflecting on the experience I look at some wider context, in particular UI/workflow and how the nature of the services mean that responses can vary.

- Listing the service outputs I provide the full text of the responses, to ground the discussion. I also provide some the second round of outputs, generated when the question was later re-run.

Asking documents questions: reflections on a simple example

Selecting a document

The choice of document matters. I had begun by looking at a political review in an area of interest, but was not confident in my judgement of outputs.

However, for pragmatic reasons, I decided to look at a professional document that I co-authored. I was confident in my ability to assess outputs and much of what I look at in this way is work-related.

Dempsey, L., Malpas, C., & Sandler, M. (2019). Operationalizing the BIG Collective Collection: A Case Study of Consolidation vs Autonomy. OCLC Research.

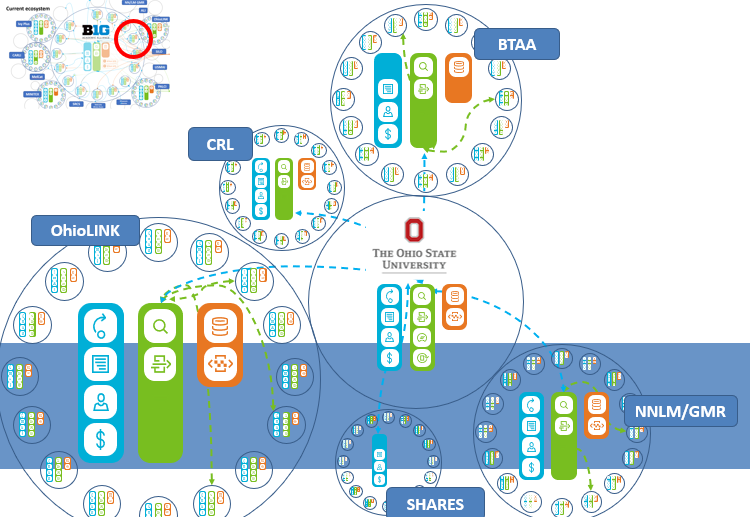

This report includes an extended treatment of the issues involved in creating a consolidated approach to the aggregate Big Ten print collection. This is an aspiration of the libraries of the Big Ten Academic Alliance, a consortium of research universities which collectively represent a major portion of the North American aggregate library collections. The report includes detailed discussion of general collaborative frameworks, the current collaborative library landscape, and some of the technical factors at play. So, while it is specific to the BTAA, it is also a general and extensive discussion of library collaboration issues.

I asked a simple question:

According to this document, what are the top four reasons library collaboration is difficult.

Here are some preparatory notes, before looking in a little more detail at the outputs.

- Prompt. The prompt is relatively open-ended. Additional prompting might have improved outputs in various ways, or I could have provided some instructions about length, tone, or some other attribute. However, I did not want to get into an exploration of the characteristics of prompting. It is also true that I could have explored whether particular approaches worked better with the specific characteristics of individual services, but again that was not my purpose here.

- Large language model. I think it is important for librarians as advisers to know what LLM is in use in a particular service and to know what policies govern the re-use of submitted materials. I was interested that this information was not more generally front and center, but required some excavation on the website or enquiry to the support line.

- Sources Some of the services provide links back into the document, to highlight relevant passages.

- Bias. Another document may have exposed more ways in which the service was influenced by omissions or by dominant, partial or harmful perspectives in the training collections. Again, that opens up interesting avenues of exploration, but more than I am doing here.

- Re-running the question. Understanding that the same question may produce different responses from an LLM, I re-ran my prompt at a later date. There turned out to be quite a bit of variation. I include the second round outputs for comparison below, but mostly limit my analysis to the first-round outputs.

- Fee vs free. I used the for-fee version of services, through either a work or a personal subscription. I did not explore what variation existed, if at all, between these and the free versions.

Looking at the outputs

The first round answers: four top-level reasons collaboration is difficult

A quick inspection of the first round of outputs shows considerable alignment in terms of the 'four reasons' presented, and in how they are described. Here is a list of reasons with a note of how many services mentioned each.

- Autonomy vs consolidation [5]

- Coordination costs [4.5]

- Interoperability [3.5]

- Diverse priorities [3]

- Local vs systemwide optimization [2]

- Efficiency vs control [2]

- Ideal vs pragmatic [1]

- Policy variations [1]

- Diffusion of effort [1]

- Decentralised US environment [1]

The 'half' scores are because 'coordination costs and interoperability' was listed as a reason by NotebookLM. Interoperability certainly does create major coordination issues (I have elsewhere called these 'stitching costs'), but, given the spread here, I thought it helpful to count separately in this way.

This is a good list which certainly reflects the arguments of the report. Given that 'autonomy vs consolidation' is embedded in the title, it is not surprising to see it top the list. The other topics are discussed throughout: none is an outlier or odd.

I just count the top-level enumerated reasons given here, per the prompt. For example, I do not count an additional systemwide efficiency which is mentioned under one of the others or think about the collective action problem, mentioned a couple of times, in this top-level set. Other reasons certainly come through in the returned narrative.

Are there any major gaps or surprising omissions? One comes to mind, and maybe it is not highlighted in the responses because it is not something that has been commonly discussed in the scholarly record or on the web. The members of BTAA consort in a variety of other organizations to get their work done, or to provide learning and development opportunities, or to lobby and advocate. An important category here is the state or regional network which may do resource sharing, negotiation, and other overlapping services. We call these 'adjacent networks' in the report. They include, for example, OhioLINK for The Ohio State University, or PALCI for Penn State. The member libraries have to manage participation across BTAA and important adjacent networks. They also raise technical interoperability issues, if, for example, resource sharing requests were to be shared. While the challenges this poses surface in general ways (coordination, priorities, ...), I would have expected it to be called out more specifically.

Looking at the first round outputs more generally

Given the somewhat open-ended prompt, I thought that all the services provided reasonable responses and was interested to see the consistency.

In general, as one would expect, there is not a lot of elaboration or nuance. While the autonomy of the libraries is mentioned, for example, only one of the responses notes that the BTAA libraries are generally large and well-resourced which is an important part of the autonomy/consolidation dynamic. I was interested to see that a couple of the responses recognized the broad way in which interoperability was used, to include organizational and social issues, while it was also seen as a more circumscribed technical issue.

There were no standout examples of hallucination. In general the responses were well-grounded in the document and were accurate and plausible in the context of the library collaboration environment described there. I wondered whether this note from Readcube Papers documentation would hold true of the approach used by the others also.

We have designed our AI Assistant to focus on answering specific questions contained within the opened research paper, rather than relying on broad knowledge trained within large language models. This can help mitigate the probability of hallucinations (nonsensical or inaccurate AI outputs), but there is always the possibility the AI may misinterpret a question or fail to extract the correct context. Accuracy may also vary depending on the topic. // Papers

How do the individual responses compare to the aggregated list of reasons? I assigned points to the reasons based on their position in the ranking, and then scored each service based on their coverage. By this simple reckoning Copilot and Acrobat, followed by Scholarcy, had most points. However, for all the reasons mentioned above, I would not lean very heavily on this. There was not a very wide spread of scores, they all did reasonably well.

Did I have a favorite in this set of responses? Entirely subjectively, I would probably chose Scholarcy. It is succinct, but also more nuanced. The four reasons are well chosen against the general ranking. But also the responses are more in the style of the report (I wondered if they were direct quotes). Somebody else who was familiar with the report might prefer the response of one of the other services.

Reflecting on the experience

Model used and training

All the services except NotebookLM from Google are using some version of GPT from OpenAI. A couple note that they access these through the Microsoft Azure OpenAI service. Scholarcy is using both Google and OpenAI models. In general it takes some excavation to find this out, and not all services publicly state the underlying model. Perhaps this suggests that the underlying LLM is seen as a commodity and so long as it works well not an important differentiator?

It also takes some work to find out if the services use the submitted documents for training purposes. Again, I was curious about this. I would have thought that some reasonable proportion of users would want to know, but perhaps not. Interestingly, Google's NotebookLM does emphasise its policy of not using submitted documents in training on its home page.

As I note below, I do think that it is important for libraries to be able to reference underlying models and service policies as they advise their users.

UI/UX: workflow, interaction, content

The actual chat interface (ChUI? - Chewy?) is pretty similar across the services: a question box and a text response. The service may provide a summary and contents by default and sometimes provides candidate further questions.

However, the services are embedded in different contexts which makes the experience rather different. For example, NotebookLM provides the ability to save responses, to work with groups of documents, and so on. Scholarcy also places this functionality in the context of a larger set of services which aim to help you 'summarize, analyze and organize your research.' In this sense, Scholarcy and NotebookLM are 'destinations' which provide a rich set of services. Microsoft Copilot, on the other hand, is available in the browser to provide responses 'in the flow' of your general activity. Readcube Papers is perhaps in between, providing a discrete service in the context of reference/document management.

In this way, workflow and context is an important factor in the choice of service and its experience.

Variation in results: not a database or search engine

LLMs generate responses based on probability distributions, statistical patterns learned from their training collections. In this way, they are unlike databases or search engines whose retrieval model is more deterministic, based on explicitly indexed data.

This means that the same prompt may generate different outputs at different times. Some other factors may also be involved.

- A service may have a 'Temperature' setting which controls the randomness of outputs. A lower temperature makes the model more deterministic leading to more consistent answers. A higher temperature makes the model more 'creative' leading to greater variability. (Some readers may remember the precise/balanced/creative toggle on Microsoft Copilot, where creative was the highest temperature.)

- The service may 'remember' context from previous conversations which influences and alters subsequent responses. This might only be in a single session or may be longer term. For example, see more about 'memory' and ChatGPT here, including the ability to switch off the memory function.

- Although it was not a factor in this example, very small changes in the prompt can change outputs.

This variability is a feature of how the services work, and is reasonable in situations like this where there is not a single answer to the question. This is one reason why it is important to get a feel for how different LLMs respond through hands on experience.

Listing the first round service outputs

Here are the outputs, with a little additional context about each service.

Microsoft Copilot

I now regularly use Microsoft Copilot for searching. I switch between Edge and Chrome, and whenever I am in Edge it tends to be my default internet search. Although, for my purposes here, of course, I just asked it to look at a single document which I loaded.

It appears to use ChatGPT 4, not the most recent version. According to these somewhat complicated notes on privacy, it does not seem that submitted documents are used for training models.

This is a good list. It leads with the issue highlighted in the report title. It uses the phrase 'collective action' but in a general sense, not picking up on the more specialized way it is used in the report in the context of the 'collective action problem.'

According to the document “Operationalizing the BIG Collective Collection: A Case Study of Consolidation vs Autonomy,” the top four reasons library collaboration is difficult are:

- Autonomy vs. Consolidation:

- Libraries often prefer to maintain local control over their collections and operations, which can conflict with the need for centralized decision-making and resource allocation required for effective collaboration. This tension between autonomy and the benefits of consolidation creates challenges in aligning strategies and policies across institutions.

- Coordination Costs:

- Managing interactions across multiple libraries and networks involves significant coordination costs. These include the time and effort required to harmonize policies, integrate systems, and manage workflows. The complexity of coordinating different institutional priorities and practices can hinder the efficiency and effectiveness of collaborative efforts.

- Diverse Institutional Priorities:

- BTAA member libraries have varying institutional missions, resource levels, and strategic priorities. This diversity makes it challenging to develop and implement a unified approach to collection management and resource sharing. Differences in institutional goals and resource availability can lead to uneven participation and commitment to collaborative initiatives.

- Interoperability and Integration:

- The technical challenge of integrating different library systems and applications is a significant barrier to collaboration. Libraries use a variety of systems for cataloging, discovery, and resource sharing, which may not easily interoperate. Developing middleware or broker services to facilitate seamless integration requires substantial investment and ongoing maintenance.

These factors collectively contribute to the difficulty of achieving effective library collaboration, as they require balancing local needs with the benefits of collective action, managing complex coordination efforts, aligning diverse institutional priorities, and overcoming technical integration challenges.

Readcube Papers

Coming into my current role, I needed the help of a reference manager. I found the shallow learning curve and utility of Papers convincing and now use it regularly. Overall, I am impressed with it. They recently rolled out an AI update which added some features including the ability to ask a PDF questions.

This is useful because you often have the PDF right there in the workflow - you do not have to load it separately. It feels like an early iteration, currently without a lot of bells or whistles.

I could not immediately see which LLM was being used (see the documentation). I queried support and received this prompt response (11/22/24): "Papers is currently using ChatGPT-4o, powered by OpenAI. This may be subject to change in the future of the app."

The document highlights several reasons why library collaboration is difficult:

- Local Priorities vs. Systemwide Optimization: There is a collective action problem where local priorities and pressures often take precedence over systemwide optimization, making it challenging to coordinate efforts across libraries.

- Tradeoffs Between Consolidation and Autonomy: Consortial working involves tradeoffs between consolidation and autonomy. Libraries, like those in the BTAA, often lean towards autonomy, which can complicate collaborative efforts.

- Diverse Membership and Needs: State consortia have diverse membership and needs, and some may lack the requisite scale to tackle the big challenges faced by research libraries.

- Diffusion of Effort: Libraries are often drawn into various collaborations to accomplish their work, leading to a diffusion of effort and making it harder to focus on a unified strategy.

Adobe Acrobat

Now, when I launch a PDF document in Chrome it opens in the Acrobat Chrome extension. Acrobat has an AI Assistant feature. Again, this means that the document chat functionality is right there in the normal workflow.

While 'diverse membership and needs' is indeed discussed across the BTAA, and while the statement below is certainly true about state consortia, the statement does not quite get at the topic discussed in the report, which is noted as a gap above.

Adobe provides more background information about its practice and policy than others. It notes that it is 'agnostic' about LLM, using the best for the task at hand. The AI Assistant currently uses the Microsoft Azure OpenAI Service, although it does not say which GPT version is used. It uses content filtering services to guard against harmful outputs and does not use customer data in training.

According to the document, the top four reasons library collaboration is difficult are:

- Coordination Costs: Managing coordination across multiple systems, libraries, collections, policies, and strategies can be complex and costly.

- Autonomy vs. Consolidation: Libraries often prefer to maintain local control, which can conflict with the need for central coordination to achieve systemwide efficiency.

- Diverse Membership and Needs: State consortia have diverse membership and needs, which can make it challenging to align around a common vision or strategy.

- Interoperability Challenges: Ensuring interoperability between different systems and services is not just a technical issue but also involves aligning policies and practices, which can be difficult to achieve.

These challenges highlight the trade-offs and complexities involved in achieving effective library collaboration.

NotebookLM

This service has been much in the news recently, in particular for its ability to re-present submitted materials in the form of a very life-like podcast. Beyond this media-friendly feature, it is actually quite useful. I especially like the ability to load a collection of documents and to query them together. However, again, here I am just looking at one document.

I can see myself using this service more. In particular, it provides a way of using the LLM search/summarise/source approach across a collection of documents at the same time.

At the time of writing, NotebookLM is using Gemini 1.5 pro, the most functional publicly available model. It also notes that it is not training on user-submitted documents; in fact this is also quite prominently declared on the home page.

Here are four reasons library collaboration is difficult, according to the source document:

- Tradeoffs between Efficiency and Control: Libraries may perceive local control as important, but system efficiency can be improved if individual libraries cede some local control to central coordination. For example, the source notes that an "Amazon-like" user experience requires removing "delay, uncertainty, and discretion from the discovery to delivery supply chain." [1]

- Ideal vs. Pragmatic: Libraries often have to pursue collaborative projects incrementally, negotiating agreements and retrofitting existing solutions rather than building new systems. The source describes how some library directors did not see a need to invest more in resource sharing, as the existing resource sharing arrangement was already "good enough." [2]

- Coordination Costs and Interoperability: Coordinating systems, libraries, collections, policies, and strategies across institutions comes with significant costs, and these costs can be difficult to manage. For example, a new library joining a network may need to adjust its policies or interwork its management system with other coordinating applications. [3, 4] The source explains that libraries must manage the coordination costs associated with participating in multiple networks, including sitting on boards and committees and adapting workflows. [5]

- Decentralized Library Model in the US: The US has a decentralized library model with little national coordination. This means that consortia often have to coordinate activities at a smaller, less efficient scale. [6] The source notes that this decentralization can sometimes hinder collaborative projects, as individual libraries may not see the need to work together when they can secure resources and services independently. [7]

ChatGPT

Of course the model which drives ChatGPT underlies various other services. Here I am using their recently released ChatGPT 4o, their most capable public model to date.

ChatGPT may use files uploaded by individuals for training purposes, although there is an option to opt out. See the documentation here. It would be helpful to date such documents.

The document outlines four main challenges to effective library collaboration:

- Balancing Consolidation and Autonomy: Libraries in consortia like BTAA value autonomy due to historical resource independence and local institutional priorities. Coordination often requires a tradeoff between centralized control (to maximize efficiency and impact) and maintaining local autonomy.

- Coordination Costs: Effective collaboration requires significant investment in coordinating systems, policies, and staff across institutions. This includes managing overlapping memberships in other networks and consortia, which can diffuse focus and resources.

- Institutional vs. Systemwide Optimization: Libraries tend to prioritize local optimization over broader systemwide efficiency. This results in collections and services being optimized at the institutional level, rather than achieving maximum collective benefit across the consortium.

- Inconsistent Policies and Processes: Variability in policies, systems, and decision-making processes among member libraries complicates the creation of a seamless, unified experience. This can slow collaboration and reduce its effectiveness.

These factors highlight the complexity and effort required to foster strong, effective collaboration among libraries.

Scholarcy

This is one of the growing number of specialist services emerging in the research/scholarly space. It has an interesting model in which it summarizes articles in a consistent way using a flashcard-style format. You can ask your own questions and it provides a selection of other services.

I could not immediately see details about the LLM in use, so I asked support. The prompt response (11/22/24): 'We use a mixture of in-house NLP algorithms and some third party LLMs including Google Gemini, and GPT-4o.' They also confirmed what is on their website, that user-submitted documents are not used for model training and are deleted once transformed into flashcards.

Top Four Reasons Library Collaboration Is Difficult

This document does not list the top four reasons library collaboration is difficult. However, it does discuss challenges related to library collaboration in the context of the Big Ten Academic Alliance (BTAA). These challenges include:

1. The BTAA libraries’ inclination toward autonomy, stemming from historical well-resourcing, established independent operations, and participation in other collaborative ventures (e.g., OhioLINK, CARLI, PALCI). This can make the BTAA a less natural venue for collaboration, diminishing incentives for participation.

2. The high coordination costs involved in managing systems, libraries, collections, policies, and strategies across the BTAA. This complexity increases significantly when considering interactions between multiple networks and systems.

3. The trade-offs between efficiency and control. While central coordination improves overall system efficiency, local control is often prioritized for political or service reasons. This conflict is particularly relevant for the BTAA which favors institutional optimization over system-wide optimization.

4. The challenges of interoperability, which is presented not as a purely technical issue, but as a complex area affected by a variety of factors, including the degree of autonomy maintained by individual institutions, the difficulty of providing a unified experience over multiple, relatively autonomous services, and the importance of consistent policies.

A concluding note

Finally, I note again that this is a simple snapshot of a small number of services. I could have looked at many more. And of course, this is only one feature of the broader range of capacities available.

Services and models are evolving quickly, as is the level of integration with existing practices and workflows.

I was interested how it was not possible to immediately see what models or approaches underlay some of the services. I do think that this is an area where libraries can be active as consumers, advocating with services that they publish details of the models used, and also their policy in relation what use is made of submitted documents.

That said, the volume and variety of these services is a signal of the challenge in this environment. Keeping track of services, let alone advising about their use, or, in some cases, licensing them, is difficult.

However, if AI does indeed become a broad-based cultural technology, as Gopnik suggests, our informational behavior will continue to evolve.

Coda: a second round of questions

I repeated the exercise a day or two later. I anticipated some changes based on experience. However, I was interested in just how much change there was. I offer this just for comparison.

I have not explored what service characteristics are at play here. For example, as noted, Copilot used to explicitly offer 'temperature' settings which were progressively less deterministic: precise, balanced, creative. They no longer offer these, but apparently can adjust based on interactions.

In the context of the discussion of the first round outputs, I was interested to see the 'collective action problem' appear as a top-level issue in the Papers output, as I had noted its absence above. I was also interested to see that Acrobat linked coordination costs and interoperability this time, as NotebookLM had in the first round. The Scholarcy reponse does this time note strong resourcing levels and other collaborative venues as dampeners within a BTAA setting, which again I note as an important issue above.

In summary, these again are good lists, with no significant hallucinations. While they vary, and while they vary from the first round, they represent valid responses.

Microsoft Copilot

The document "Operationalizing the BIG Collective Collection" outlines several challenges to library collaboration. Here are the top four reasons:

- Autonomy vs. Consolidation:

- Libraries within consortia like the BTAA (Big Ten Academic Alliance) often value their autonomy and have historically operated independently. This independence can make it difficult to consolidate resources and strategies, which is necessary for effective collaboration.

- Coordination Costs:

- Managing coordination between multiple libraries involves significant costs, including time and resources. These costs arise from the need to align policies, systems, and workflows across different institutions, which can be complex and resource-intensive.

- Diverse Institutional Priorities:

- The member libraries of a consortium often have varying priorities and missions. For example, some may focus more on research while others prioritize undergraduate education. These differing priorities can lead to challenges in aligning goals and strategies for collaboration.

- Policy and Strategy Alignment:

- Effective collaboration requires a high degree of alignment in policies and strategies, which can be difficult to achieve. Libraries may have different policies regarding resource sharing, collection development, and other key areas, making it challenging to create a unified approach.

Readcube Papers

The document does not explicitly list the top four reasons why library collaboration is difficult. However, it does mention several challenges and considerations that can make collaboration complex:

- Tradeoffs between Consolidation and Autonomy: Libraries often face tradeoffs between working collectively and maintaining their autonomy, which can complicate collaboration efforts.

- Diverse Membership and Needs: State consortia have diverse membership and needs, which can make it challenging to address the big challenges faced by research libraries.

- Decentralized Political Environment: In a decentralized political environment, national provision is rare, making it difficult for libraries to collaborate on a large scale.

- Collective Action Problem: Local priorities and pressures often take precedence over systemwide optimization, presenting a classic collective action problem.

These factors highlight the complexity and difficulty of achieving effective library collaboration.

Adobe Acrobat

According to the document, the top four reasons library collaboration is difficult are:

- Tradeoffs between consolidation and autonomy: Libraries often have to balance between consolidating resources for efficiency and maintaining autonomy to meet local needs. This can create tension and make collaboration challenging.

- Coordination costs and interoperability: Coordinating systems, policies, and strategies across multiple libraries and networks can be complex and costly. Interoperability is not just a technical issue but also involves aligning different policy regimes and operational practices.

- Variability in institutional priorities: Different libraries have varying priorities based on their institutional missions, which can lead to differing levels of commitment and participation in collaborative efforts.

- Need for explicit commitments and shared processes: Effective collaboration requires clear commitments, shared strategies, and common processes for decision-making and resource allocation. Without these, it is difficult to achieve cohesive and efficient collaboration.

NotebookLM

Here are four reasons, according to the sources, why library collaboration is difficult:

- Coordination costs are often underestimated. For libraries to collaborate effectively, they must agree on common policies, integrate their systems, and share responsibility for collections. This requires a significant investment of time and resources, especially in the context of an already complex library ecosystem with pre-existing relationships. [1-6]

- Libraries may not have strong incentives to collaborate. Many research libraries, including BTAA members, have significant resources and capacity to operate independently. Therefore, the benefits of collaboration may not always outweigh the perceived costs of surrendering local control. Libraries also have other avenues for collaboration, such as state or regional networks, and may prioritize those relationships over broader collaborations. [7-11]

- Differences in institutional priorities and policies can make it difficult to agree on a shared approach. Each library has its own unique mission, user base, and collection strengths. This can lead to a diversity of needs and priorities, making it challenging to achieve consensus on a collaborative strategy for managing, building, and sharing collections. For example, different institutions may have different levels of commitment to preserving print collections or investing in shared infrastructure. [8, 12, 13]

- Collaboration often involves trade-offs between efficiency and local control. Centralized coordination can improve the overall efficiency of a library network, but it may also require individual libraries to relinquish some control over their collections, policies, and workflows. This can be a difficult decision for libraries that are accustomed to operating autonomously, and it may require careful negotiation and compromise among stakeholders. [11]

ChatGPT

The document identifies four primary challenges that make library collaboration difficult:

- Autonomy vs. Consolidation: Libraries are used to operating autonomously and may prioritize local decision-making and strategies over consortial goals. This makes it challenging to align efforts across multiple institutions(operationalizing-the-BI…).

- Coordination Costs: Managing collaborations requires significant investment in time, staff, and resources for coordination, which can strain individual institutions and reduce efficiency(operationalizing-the-BI…).

- Diverse Affiliations and Priorities: Libraries often belong to multiple consortia and networks, each with its own goals and requirements, leading to competing commitments and diluted focus(operationalizing-the-BI…).

- Inconsistent Policies and Systems: Variations in policies, workflows, and technology across libraries hinder interoperability and make unified efforts more complex and less effective(operationalizing-the-BI…).

Scholarcy

According to the document, the top four reasons library collaboration is difficult are:

1. Autonomy vs. Consolidation: The BTAA libraries lean toward autonomy due to their historical well-resourcing and other collaboration venues. This autonomy can weaken incentives for collaboration within the BTAA, as libraries are used to acting independently and may not see BTAA as the first venue for collaboration.

2. Coordination Costs: Managing coordination costs of partnering with multiple groups is challenging. Libraries are embedded in multiple networks, which can compete for attention, staff time, and resources, making it difficult to align efforts.

3. Diverse Membership and Needs: State consortia have diverse membership and needs, which may not have the requisite scale to tackle the big challenges research libraries face. This diversity can make it harder to align around a vision of shared library services or infrastructure.

4. Lack of Systemwide Optimization: BTAA collaboration around collections is generally secondary to institutional planning, with local control often taking precedence over systemwide optimization. This results in collections being optimized locally rather than at the BTAA level, which can hinder more effective collaboration.

Picture: The feature picture is from an illustration in the report, created by Constance Malpas.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to my colleague Ben Lee for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Update: Introduction slightly updated to note library influence and specific focus 12/4/24.

Note: See this link for posts on AI, including some deeper dives into models, library contexts, and other topics.

For those interested in the report itself, there is a summary outline in this post: