I was in a meeting with a group of folks from research libraries the other week. I was interested in a particular terminological issue: ‘ebooks’ and ‘digital books’ were each being used in conversation. I asked was there a pattern of consistent use here. ‘Not complete consistency’ was the answer, but there was certainly a tendency to use ‘ebooks’ for materials available for license from external providers, and a tendency to use ‘digital books’ for materials digitized from library collections.

So, in this context, it is easy to see how each expression has a different – if overlapping – set of associations. Ebooks may evoke an environment currently fragmented by provider platforms, with restrictions on use, and managed in a licensed e-resource workflow. They are for reference, information, reading. Digital books may evoke a digital library environment, an aspiration to provide higher level research services based on text mining, entity identification, and so on, and various funding and cooperative initiatives which aim to increase the corpus. The Monk Project or the international Digging into Data Challenge are examples of a direction here.

Over the next few years, it will be interesting to see how these environments evolve as ebooks/digital books grow in number and usage. Ebooks and digital books – to continue to use these ambiguous terms – will become more important in the practice of research and learning. There are at least three big drivers in the environment the group above was discussing. The first is around moving physical collections to the cloud as libraries balance service between local collections, shared offsite collections and digital collections. There are early discussions about policy and service frameworks within which libraries can reduce their print inventory and the opportunity costs associated with it (see here for example). The second is around the demand environment, as books in digital form offer a better fit with research and learning workflows which are increasingly network based. The increasing availability of books in digital form supports patterns of discovery, analysis and use now common with other resources. Think for example of the practice of ‘strategic reading’ (or ‘reading avoidance’) where researchers are found to prospect the literature broadly in a digital environment, searching, consulting abstracts, scanning for terminology, diagrams and so on (interestingly described by Renear and Palmer here). For many purposes, people will prefer the digital versions and will shift use. This is not to say that people will not continue to read physical books, but it is interesting to consider the pattern of adoption (and continued development) of the journal literature. The third is around the environment of supply, where there is major current activity. The post settlement Google Books institutional product offering, Amazon’s attempt to ‘iPodify’ books, the rise of the iPhone, and a range of other developments point to rapidly changing opportunities.

So the relationship with the book literature is going to change in significant ways, which may make the ebook/digital book distinction advanced above less relevant. In fact, Google Book Search already moves beyond it in important ways. And libraries are exploring various syndication models (with Amazon, for example, or Kirtas) or in collaboration with publishers such as the the Cambridge Library Collection, for example. Fragmentation, of technical platform, of format, of business model, and so on, will complicate service provision..

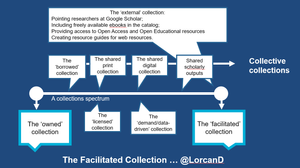

This poses major questions for libraries at all levels. From a (current) workflow point of view, we will see a shift of more activity out of the ‘bought’ materials workflow into the ‘licensed’ materials workflow. From a collections point of view we will see a rebalancing between local, shared and third party print and digital provision in ways now being worked through. There are bigger issues, already with us with the journal literature, about the curation of the scholarly record, about sharing of materials, and about assuring the type of access that is compatible with use and re-use in research and learning.

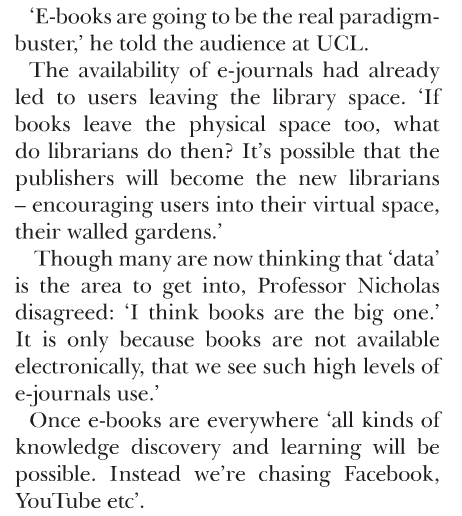

I was very interested to read the following remarks by David Nicholas in Update (behind a member wall) recently …

I think that libraries may be underestimating the impact and pace of change in the book world …

Share

More from LorcanDempsey.net