We are used to buying books. To sharing them. To giving and receiving them as gifts. To quietly marking them. Even sometimes to proclaiming ownership in a bookplate. We are used to copying parts of them for study, to quoting from them.

Books circulate – through libraries, private collections, bookstores and used bookstores. They are sold and resold. They exist redundantly: multiple copies are issued and they can be tracked down in various places.

A by-product of this redundancy is the persistence of the scholarly record: lots of copies keeps stuff somewhere.

My Concise Oxford Dictionary offers ‘prepare and issue … for public sale’ as a definition of ‘publishing’. ‘Publishing’ is a making ‘public’, and the materials published are available to the public in various ways. They are also available for use and disposal at the buyer’s discretion.

However, this line of thinking may sometimes mislead. For example, John Sutherland, distinguished critic and historian of literature, writes about the Google digitisation initiatives and the announcement of Microsoft’s support for digitization at the British Library:

What is coming is something akin to the Oklahoma land rush of 1899. A half-dozen massively wealthy digital pioneers all going hell for leather to “propertise” the hitherto democratically owned “public domain” – that deposit of printed material that currently (but not for much longer, alas) you, I, and nobody own. It will be the biggest privatisation in history, and the most profitable. Once the public domain is propertised, it will remain proprietary material forever. [EducationGuardian.co.uk | E-learning | Ivory towers will fall to digital land grab]

He goes on to talk about the knowledge base of the university, and how it “is added to and refreshed, in the form of new books for the library and so on” and says “but it is essentially a university-owned asset.”

But it is not a university-owned asset, or it is only partly a university-owned asset, if by ‘own’ we imply unrestricted use and re-use. ‘Publication’ does not put materials into the ‘public domain’; they are only in the public domain when copyrights expire or are not in place. The ongoing proprietary interest of the copyright holder has always been something that libraries have managed, and its interpretation, as we know, has sometimes been a cause of tension between publishers and libraries. Like books, journals were published and distributed, and often have institutional and personal subscription rates which recognise institutional and library patterns of use. In the print world, however, even when copyrights were still in force the sharing, distribution, and occasional re-sale of the materials could make institutional ‘ownership’ more visible than the ongoing proprietary interest of rights holders.

Of course, moving into the digital arena changed this. And we have seen with journals a very different model emerge where institutional ‘ownership’ has given ground before the proprietary interest of the copyright holder. ‘licensing’ has replaced ‘buying’ as the visible model. And there is an ongoing library discussion about appropriate models for sharing and preserving journal materials which are not now ‘owned’ redundantly by libraries.

Two recent initiatives have made this type of discussion of much more general interest. The first is the mass digitization initiatives of Google and others where the interests of the copyright holders has been asserted, questioning whether the Universities can in fact do as they will with the ‘knowledge base’ that they have acquired.

The second is more recent still and is more interesting given its potential impact. As people realize what restrictions they face when they ‘buy’ music on iTunes, the changing nature of ‘publishing’ will become apparent. In many cases ‘rent’ may be a more apt description than ‘buy’. And from music back to books, here is Adam Green:

While waiting in my dentist’s office this morning I started reading BusinessWeek and came across a story about Sony’s new ebook reader. The hardware sounds nice, but there is no way copy-protected ebooks are going to succeed. As I keep telling my kids when it comes to music, if there is DRM you are renting not buying. A day will surely come when you switch hardware or the company switches DRM schemes and your music will go away. Personally, I don’t care that much about music, but when DRM is applied to books I get a little crazy. For book buyers owning the book is at least as important as reading it. I’m not even going to talk about the way books smell or the way they feel in your hands. I accept that digital books may replace physical ones, but interfering with my ability to own a book, and even pass it on to my kids or future grandkids is not something I will tolerate. When people predicted the effects of computer technology on society 20 years ago, nobody imagined that software licenses would eventually spread to books and music. I’ll predict now that ebooks will never become popular while DRM is in place. [Darwinian Web: Adam Green’s thoughts on the evolution of the Internet]

So, moving forward we are looking at an environment where individual consumers will become more aware of the issues of the shift in models, and some pressure to change may come as a result.

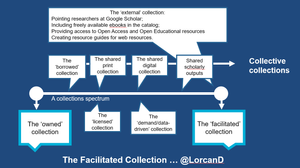

For libraries, in addition to current access issues, it highlights the longer term question of what their responsibility to the cultural and scholarly record is, and how it will be discharged. In the print world, the ‘publication’ and distribution of multiple copies of materials, and the individual behavior of libraries and related institutions, have resulted in a collective record lodged in many individually curated collections. Some few institutions have significant parts of this ‘knowledge base’, readily accessible to their users. With persistence, a large part of the collective ‘knowledge base’ is accessible through catalogs, bibliographies, finding aids, and so on.

The changed pattern of distribution of digital ‘publications’ will need a different model, one which requires more concerted systemwide strategizing and action.