- The powers of library consortia 1: How consortia scale capacity, learning, innovation and influence

- The powers of library consortia 2: Soft power and purposeful mobilization: scaling learning and innovation

- The powers of library consortia 3: Scaling influence and capacity

- The powers of library consortia 4: Scoping, sourcing and right-scaling

In the previous blog posts in this series, I have spoken about four areas where consortia scale library capabilities: capacity, learning, innovation and influence. In considering general consortial or group activity and its relation to institutional investment (of dollars or of attention/expertise), the opening post also introduced three important axes where choices are made: scoping, sourcing and (right)scaling. Here, I amplify those introductory remarks.

While the range and diversity of consortial activity is enormous, some of the important ways in which they are different relate to these three axes. Again, given that diversity, this is a preliminary and impressionistic discussion.

Scoping

What should consortia do? What is the right scope?

Single or multipurpose? As discussed in the first post in this series, there is an interesting balance between economies of scope (where, for example, it makes sense for members to concentrate a variety of different functions with an organization, PALNI being one example) and economies of scale (where the costs of providing a service, including infrastructure, marketing, R&D, etc., are spread across many participants, as in HathiTrust). The former case may favor the trend I have already noted, where a consortium evolves into a general collaborative vehicle that members reflexively turn to when new or shared needs arise. Of course, this does not mean a consortium can do everything – there is a cap depending on resourcing, and libraries have to decide how much resource they transfer into a consortium, how much of their staff time is devoted to committee and collaborative working, which of their activities might be shared across consortium members, and, indeed, which consortia to turn to for which needs.

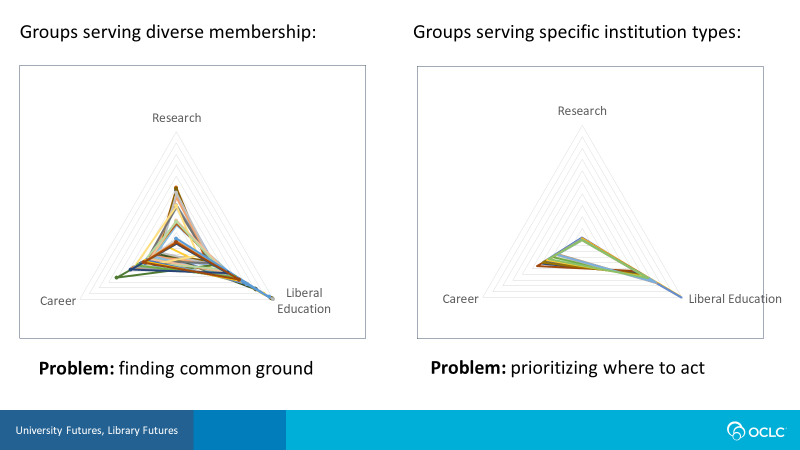

Peer or multitype. The intersection of interests between members of a consortium is an important driver of priorities and activities.

Consider for example these two pictures, which represent the parent institutions of two academic library consortia. These are drawn from our University Futures, Library Futures work, where we have developed a method to characterize higher education institutions based on IPEDS data. We characterize universities based on their distance from three poles: research, liberal education, and career-preparedness. The triangles show how individual universities are positioned relative to these poles. The analysis here shows clearly how the libraries in one consortium support broadly peer institutions (on the right, where the triangles overlap), while the libraries in the other support universities with a spread of emphases (on the left, where the triangles diverge).

In a group of peers, the intersection of interests may be broad, and members may look to the consortium across a variety of activities. In this case prioritization becomes an importance consideration. Where the intersection of interests is smaller (because of size or type of institution, for example), then the common areas for consortial attention may be more limited (focused on resource sharing, for example). And in this case, finding those common areas of attention becomes important.

Right-scoping and optimization. It does not make sense for all organizations to operate equally across all four areas I have mentioned – each requires different skills and orientations, and it is difficult to optimize across all. For this reason, right-scoping is a critical issue – which activities does it make sense to pursue?

Think of capacity and influence, for example. Scaling capacity benefits from an operational focus and economies of scale. Scaling influence involves political and advocacy skills, the broadest possible base of representation to give weight to assumed positions, and agility across a potentially broad range of areas. So, in each case success requires very different attributes and it may not make sense – or be possible – to optimize a single organization for both together.

Does this suggest that organizations should not try to scale both capacity and influence? In this context, one could argue it made sense for RLUK, for example, to transfer the management of COPAC (union catalogue) to Jisc (who is now contracting with OCLC to provide the service), because, as a strategic organization, it makes sense for RLUK to scope its activity towards influence and innovation, not operational services (capacity). What about CARL and Portage, or ARL and SHARE? In each case the organization has played a central role in incubating an approach (scaling innovation); does it make sense for the organization to actually run the service long term (scaling capacity)? Not least, this would present a significant opportunity cost, but it may also tie up a whole range of capacities and investments. Does it make more sense to continue to encourage learning and innovation within the powerful network each organization manages? And to work with partners to operationalize such services?

As noted above, advocacy – scaling influence – was a critical part of the early development of HathiTrust. It was pushing policy boundaries, and it probably needed to be in advance of positions taken by community organizations focused on scaling influence. While these policy issues remain important, HathiTrust is increasingly likely to work with and through those organizations (e.g. ARL or ALA) to scale influence, so that it remains very focused on scaling capacity, on the operation of a major service and its sustainability.

So, I think that there are interesting questions for groups who would like to scale both capacity and influence, to build shared services and to lobby for change. However, organizations which scale capacity or influence are both now increasingly important venues for scaling learning and innovation. As already discussed, a major reason for this is that they convene networks of libraries, within which shared practices can emerge.

Those organizations set up to encourage systemwide change are an interesting example. These seek to scale influence, providing a shared advocacy and lobbying focus. Think of scholarly communication, for example. SPARC has a change agenda. COAR is a membership organization supporting the development of green open access, by supporting the emergence of networks of repositories. In each case, scaling innovation is the goal but scaling learning is also critical, as they wish to provide members with evidence and argument in support of change.

Continuity and evolution. Organizations need to evolve and scoping questions will be affected by the changing environment and needs of members. The evolution of shared print has been interesting here, where in some cases a shared print program has been taken on by existing organizations (e.g. BTAA), while in others new organizations have formed (e.g. WEST). In this way, just as scoping is an issue for existing organizations, so it is an issue for new organizations. When does a specific need lead to a new organization rather than the evolution or adaptation of a current one?

One response to this, particularly aiming to scale, strengthen and focus innovation, is the emergence of Educopia, Duraspace, and other organizations as incubators for new initiatives seeking to spread cost and risk. Ithaka was also established with an explicit mission to incubate non-profit startups in the education space.

Libraries and consortia will think about disinvesting and investing. When should a group cease to exist, or give up particular activities because they are sub-scale or no longer make sense? This can be difficult, given natural organizational inertia, and existing personal and institutional investments.

At the same time, consortia may grow, whether by adding members (by expanding into adjacent geographic regions, for example), by securing more investment from members (by expanding scope, for example), or by diversifying funding (by providing for-fee services to non-members, for example, or by seeking grant funding). As discussed in the opening post, a diversification of funding may result in some diversification of accountability. This in turn raises issues of governance, to make responsibilities and accountabilities more explicit.

Sourcing

I noted in the first post that there are three common patterns through which shared services are sourced: public provision through national/state coordination and/or funding; consortial activity; and third-party provision (through a vendor).

Of course, each has its own characteristics, which may be variably present in any individual case. And each approach will have benefits and drawbacks. Public provision is a useful way of securing shared infrastructure, but community influence may be lacking or management may be bureaucratic. Consortial activity gives responsibility to members but coordination costs may be high. With a third party, control is exercised through contractual relationships, but direct influence may be surrendered for efficiency. And so on.

My focus in these posts has been on the second of these, the consortial model, acknowledging that in practice the three overlap or blend into each other, and will often occur in combination. In particular, of course, the first two will often procure services from the third to achieve their goals. OhioLINK or the Orbis Cascade Alliance, for example, will source some systems capacity with third parties.

There are two levels of interest here. First individual libraries have to make choices about how to source a shared service – do they look to a consortium or a vendor? Do they encourage a national provider – e.g. Jisc or the National Library of Australia – to provide a service? Do they establish a new consortium around a particular need (e.g. Library Publishing Coalition or Open Textbook Alliance)?

Second, consortia have to decide how to source services – do they build them themselves, look to a third party, look to a center of expertise within the consortium, and so on.

In practice, the issues in each of these cases can be similar. Here, I am mostly interested in the issues libraries face in terms of electing a consortial approach.

As the trend towards collaborative systems and services grows, sourcing issues come to the fore and libraries and consortia will more actively manage organizational frameworks around collaborative service development. A variety of issues is important here.

Structure, staffing, organization. Is the group organized to get the desired job done? One aspect of this is the accumulated trust that seems to be so important in streamlining decisions and actions. Another is governance: is the group organized to efficiently make binding decisions? A recent presentation noted the challenges of making decisions within the Ivy Plus group given the lack of a formal governance structure, for example.

Agency. A second aspect relates to agency, also discussed in the first post. Is some new organizational arrangement required to advance a collaborative agenda? This in turn raises the question of when a separate organization should be set up (as has happened with various new shared print initiatives in the US) or whether an existing center of excellence assumes responsibility (as has happened to some extent with the University of Michigan and HathiTrust, where the University hosts and operates the service on behalf of the membership).

Some collaborative activity may be based on closely supervised activity – relying on temporary staff assignments and local resources. A contrasting approach is to buy a complete service from a third-party provider. Clearly, in between there are variably structured approaches depending on how resources, staffing, and so on are secured across the group. This points to a crucial issue, which is the balance between efficiency and control. One wants to ensure alignment with the original mission while also ceding sufficient authority to the consortium management to advance without continued checking.

As noted in the introduction, the dynamic changes as a group gets bigger (and it is inefficient for all members to participate equally in decision making), or more complex (in terms of types of members or sources of funding, for example), or changes over time (as when founding members or strong guiding voices recede or are replaced).

These issues make frameworks for governance, accountability and alignment very important , and they need to address topics like scope, evaluation, ownership of data or IPR, development of requirements, sharing of innovation, and so on.

Resourcing. One might note that collaboration and shared infrastructure are not cheap. And greater collaboration involves greater investment in shared activities. But what is the appropriate level of investment here? And how do libraries think about where best to invest?

I would argue that we do not have a good sense of levels of investment in different collaborative activities at the moment, nor do we have a sense of what level of investment is appropriate. And inevitably libraries are differently situated with respect to collaborative work – a library which is part of a strong regional or peer consortium with a track record of shared investment and new service development is in a very different situation to one which is not a part of such a consortium.

As a community, we also incur considerable development costs around the design and development of new organizations. And while organizations like Educopia, Duraspace or others provide incubation services, the community as a whole does not have robust support for this, nor are there strong mechanisms for coordinating new initiatives.

All of this confirms that sourcing will be a subject of increasingly active debate in coming years, and issues of mission, alignment, governance, investment and business model will become more central in a mixed environment of collaboratively and externally sourced provision. It also means that choices around sourcing patterns need to become more informed. When should a group build a new activity itself or source it with a third-party provider? When should an individual library buy a service from a third party or instead participate with a consortial group to develop a similar service that is more community-driven? What level of coordination would be helpful, and how could it be enacted?

Sourcing and scaling are intimately connected. As libraries explore collaborative solutions, they need to decide at what scale to participate.

Right-scaling

In many ways consortial or group working is about right-scaling, finding the appropriate level at which to do something. Groups must decide what the optimum level for their work is. And individual libraries must decide at what level to consort in the context of any particular activity. There are three common patterns in the consortial examples I have given in these posts:

- regional/national groups which scale to a particular region or jurisdiction,

- functional or peer groups which may operate at different scales,

- groups where achieving as broad scale as possible is important, to aggregate influence or to build community infrastructure.

And of course libraries may belong to groups at all of these levels.

The regional grouping is a very common pattern for organizations that scale capacity. This may be at a country level (see UKB in The Netherlands, for example), at a state level (see OhioLINK for example), or within some other contiguous area (see the Orbis Cascade Alliance, which spans the states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho). It seems likely that one reason for the strength of local or regional groups is that that they facilitate informal learning and innovation through their networks, something that may be less strong at wider levels where personal interaction within a ‘known community’ is less strong.

Regional groupings are also very important in relation to shared infrastructure, a shared ILS for example. An interesting recent development has been the emergence of groups built around shared print management: typically, these have a regional logistics dimension as infrastructure for consolidation and delivery is important (WEST, EAST, MI-SPI, FLARE, White Rose Consortium, for example). However, the emergence of the Rosemont Shared Print Alliance in the US suggests that higher level coordination is also desirable. And certainly, one wants aspects of this work to scale to the network level in the context of stewardship of the (national or global) print scholarly and cultural record.

While the regional dimension remains strong, and may be reinforced by state or national funding, we also see examples where sustainability, service or other factors encourage growth and collaboration. For example, resource sharing networks may talk to each other, or a consortium may grow beyond its regional base. This is exemplified by NERL, which has grown its core membership beyond the North East United States, and has also added an affiliate category for libraries who are not core members but who want to participate in some of the benefits of shared negotiation.

Typically, libraries scale influence at the level of a particular political entity where policy is made. So, it is typical to have representative associations at the national level (ALA, ARL, ULC; RLUK, CILIP, SCONUL, CAUL; and so on), or, in the EU for example (LIBER).

And, as noted above libraries come together in various peer groups (e.g. BTAA, acknowledging that this sits under the parent BTAA organization) and functional or specialist groups (e.g. DPC, DPN), at various scales.

Right-scaling is of great current interest, even if it is not usually designated this way or explicitly called out in discussion. I conclude with two important right-scaling issues.

First, libraries need to decide at what scale certain activities should be carried out (scalar emphasis) – and the answer may be at several. Think of shared print or research data management for example, each of very focused interest now. Libraries may make investments at local, consortial, national levels, or with third parties. For example, Ohio State University is part of the OhioLINK, BTAA and HathiTrust shared print regimes, and will have to think about the nature and level of participation in each over time. Monash University provides local workflow for research data management through a third-party provider (FigShare) while at the same time it backs up data to a state-wide system and relies on a national scale service for discovery. Such multi-scalar activity will become more common, and again poses investment and service choices.

Second, despite considerable collaborative activity libraries face a collective action issue, which works against scale. There are many libraries, each with its own goals and objectives, and coordination costs are high. One of the main advantages of the regional consortium – or of national frameworks in countries that have them – is that they entail some coordination capacity. However, this coordination capacity is often lacking at higher levels, nationally within the US, for example, or internationally. For this reason, broad based network-level shared infrastructure is lacking. Cameron Neylon writes interestingly about this: “Any proposal that starts ‘we’ll just get all the universities to do X’ is basically doomed to failure from the start.” That is, they are doomed unless, he suggests, coordination mechanisms are actually built in.

Neylon is writing about scholarly communication infrastructure, and, in fact, scholarly communication is an interesting example for library cooperation. There appears to be growing consortial interest in research support infrastructure (research data management, scholarly publishing platforms, ….), as libraries are not always well-placed to develop approaches individually. See for example the work of the Scholars Portal in Ontario, one of the clearest examples of research support offered consortially.

What gives the topic some urgency, though, is recent developments in research workflow services and questions about sourcing the means of scholarly production with such services. In particular, the progressive acquisition of research workflow and administration services by Elsevier (e.g. bepress, Mendeley, SSRN, Pure, HiveBench) has highlighted issues of ownership and control. In parallel the Holtzbrinck family of services (which includes Springer Nature and the Digital Science portfolio of research workflow and productivity services) has also highlighted the growing interest of the larger publishers in research workflow. Workflow, one might say, is the new content.

As Neylon argues, a small number of large publishers can decide on direction and move quickly, in a way that collaborative initiatives often cannot.

Against this background, it is interesting to note David Lewis’s proposal that libraries collectively contribute a portion of their budget to support community-based scholarly infrastructure providers in a more coordinated way. This potentially addresses both a coordination and an investment problem, although to levels which are probably unprecedented.

It remains the case, though, that while libraries collaborate massively, massive library collaborations are rare. In terms of scaling influence, there are several trans-national organizations (IFLA and LIBER for example). In terms of scaling infrastructure, OCLC has built a network of thousands of libraries around the world but is a striking exception. In this context the future of Hathi Trust is intriguing – will it be sustained as a part of global library infrastructure and what is the path towards that? Will DPLA and Europeana find a way to sustain operations as a crucial part of shared library infrastructure, beyond the funding impulses in which they started?

Conclusion

In this series of posts, I have given examples of how libraries consort to get their work done. They have a long history of collaborative activity of different kinds and at different levels. There is a huge variety of consortial organizations. The US environment is especially complex, as libraries potentially collaborate in multiple layered arrangements.

I have had two purposes.

- I argue that it has become centrally important for libraries to find good ways of scaling learning and innovation, so as to remain responsive to the changing behaviors and expectations of their users.

- I want to suggest some ways of looking at consortia, notably thinking in terms of two simple schematics. First, I have suggested that consortia help scale influence, learning, innovation and capacity across libraries. And, second, that scoping, sourcing and right-scaling are important axes of choice as consortia position their services.

Here are some concluding observations …

Consortial issues are underexamined …

- Despite this history and extensive descriptive discussion of consortia, the broad shape of consortial activity is surprisingly under-explored in terms of organizational development and economics. There is a broad general literature on related topics and much relevant activity in other domains which could be usefully looked at.

- From one perspective, it is not surprising that there are open questions about consortial activity. Collaboration is difficult. Parent institutions are focused on local value, and it may sometimes be difficult to justify or explain investment in cross institutional activity. Requirements change in ways that don’t always align with consortial evolution. It may be challenging to take a systemwide view from an individual library perspective. However, there are some striking areas where we might have greater consensus.

- These include agreement about appropriate levels of investment in shared activity, patterns of when and how to consort, models of successful consortial activity, and a view of optimum sourcing and scaling choices in particular circumstances. And, critically, about network level shared activity (where the network is at national or higher level).

Scaling learning and innovation is a central driver …

- The research and learning practices of library users are changing, the information environment is diversifying, and cooperative service opportunities are amplified, all under the influence of network and digital approaches. The imperative to understand this environment and to evaluate appropriate responses is strong.

- Groups play an increasingly central role as they mobilize their networks to scale learning and move innovation into practice. Learning and innovation are emergent features of shared practices and interaction.

- The soft power of consortia to convene and scale learning and innovation should be explicitly encouraged, acknowledging there will be increased competition among venues with a specific focus on scaling learning and innovation.

Libraries will need to rationalize their affiliations …

- Collectively libraries invest a major resource in maintaining and participating in consortial organizations. It may seem that the opportunity costs of participation are sometimes too high, that the general lack of planned coherence can be a drag on development, that effort may be diffused across redundant organizations with unclear scope. And that all of this can prevent any one organization from achieving the scale efficiencies or impact that are really possible.

- At the same time, additional investment in shared capacity may actually be needed to achieve the benefits libraries need most.

- This creates an inevitable tension: libraries need to collaborate more, and more effectively, and need better organizational frameworks to do so; yet they may find that the current configuration of collaborations is not yielding the desired results. Accordingly, there is a feeling that libraries participate in shared activities both too much and not enough.

- However, it is not simply more collaboration that is needed – it is a strategic view of collaboration, especially where there are new infrastructure demands (for example, for shared digital preservation, web archiving or research data management), increased challenges for advocacy (around value and values), and growing competition between libraries and other network information service providers (for example, for research support services).

- This underlines how individual library reliance on consortial activity is variable. And we should see libraries become more purposeful about what portion of their budget to earmark for collective activities that advance their mission faster, more cheaply, or otherwise more effectively than going it alone, and about ensuring that those dollars are directed to the organizations that can achieve what is desired.

Libraries can scale services and influence in several ways. The consortial approach will remain a central if challenging choice, all the more challenging as libraries need to work hard to work together effectively.

Acknowledgements. I am grateful to the following people for generous comments on earlier drafts: Gwen Evans, Mike Furlough, Kevin Guthrie, Susan Haigh, Brian Lavoie, Kirsten Leonard, John MacColl, Constance Malpas, Barbara Preece, Judy Ruttenberg, Katherine Skinner, John Wilkin, Nicola Wright. Of course, I alone am responsible for the use to which I have put their advice and they do not necessarily share any of the views expressed here! I presented some of this material at the JULAC 50th Anniversary Conference in Hong Kong, and I benefited from the views outlined in the formal responses of Peter Sidorko and Louise Jones. I am especially grateful to my colleague Constance Malpas for extensive commentary.

Picture: I took the feature picture of St Ignatius of Loyola at Xavier University. Xavier is a member of OhioLINK, which has been a pioneering library consortium.

Note: I made some cosmetic amendments including addition of feature picture and headings on 20 March 2021.