Driving around Ohio: the scale and diversity of the US university system

When we first came to the US, we were keen to explore. We drove around Ohio and gradually widened our radius over long weekends and other breaks. Indeed, we did this for quite a while … pretty much until the children protested and would no longer let us. One feature helped pattern our trips: the presence of a university or college. This was not especially limiting, because it seemed there was a university around every corner.

We were amazed by the richness of the US university system, and by its diversity in so many dimensions – size, setting, mission, focus, public/private. Ohio University dating from 1804 is the oldest University in Ohio, located in Athens, a relaxed college town opening up to an Appalachian hinterland. There is great variety in the thirteen other public universities in the Ohio system, which includes institutions with a strong regional focus, as well as those which attract international attention. The University of Cincinnati’s ambition is evident in its fine campus marked by signature ‘starchitect’ buildings. There are Kent State and Bowling Green universities; Cleveland State, Akron and Youngstown State in urban rust belt settings; Miami (get the t-shirt: “Miami was a university before Florida was a state”); and others. The youngest university in the system is Shawnee State, founded in 1986, “offering a highly personalized, affordable, and accessible education dedicated to the exploration of emerging technologies and emerging ideas.”

Of course this system also includes The Ohio State University, an academic powerhouse which sits in the global circuits of research and scholarship, as well as being central to the economic, social and cultural life of Columbus and Ohio. These large land-grant public institutions are a major achievement of the US system.

There are the well-known liberal arts colleges in picturesque chocolate box settings (Kenyon, Wooster, Denison, Oberlin). There is a leading private research university which is an important anchor in the cultural and educational quarter of Cleveland, Case Western Reserve University.

But beyond some of these better-known institutions, there is the very broad range of small private colleges dotted across the state, such as Urbana University (home of the Johnny Appleseed Museum), and the two, yes two, universities in Tiffin, Ohio. Tiffin is home to Heidelberg University, a liberal arts college, and Tiffin University, a private university which “provides a personal and practical education for motivated students who want real-world experience and results.” “There are no ‘ivory towers’ at Tiffin University” as it says on its website. We were also interested in the importance of religious communities, and how many universities offer an education in an explicitly values-based setting. One thinks of the Franciscan University of Steubenville or Ashland University (“affirms Christian values as a core element of the University’s institutional identity”).

This is just a brief reminder of the scale and diversity of the university system. I emphasize it, because when we talk about higher education we sometimes overlook this variety. And of course, this is just to look at the non-profit four year system. It does not consider community colleges (who of course have an important relationship to the public university system), for-profit institutions, and others.

This variety is now part of the intense debate about mission, organization and direction in higher education. This is driven by multiple factors, including sustainability, affordability and inclusion, research evaluation and the associated influence of rankings, and increased recognition of the diversification and distinctiveness of mission. Universities are making choices about direction and focus, and thinking about how to differentiate themselves.

As universities change and grow, so do libraries. And there is a very active discussion about academic library directions. Against the university background sketched above, such discussion shares two interesting features.

First, it sometimes proceeds without reference to the universities of which libraries are a part. However, the report argues that the most important long-term influence on the library is the requirement placed on it by changing patterns of research and learning. These changing patterns, in turn, are shaped by the focus of the parent university or college and the directions it is taking.

This presumption of homogeneity encourages a view of academic libraries in which the research library is seen as a terminal point in evolution, rather than as one type among others. However, where universities and colleges seek to differentiate themselves this presumption is increasingly misleading.

Second, it often presumes some homogeneity of approach or direction, different only in degree among libraries. This presumption of homogeneity encourages a view of academic libraries in which the research library is seen as a terminal point in evolution, rather than as one type among others. However, where universities and colleges seek to differentiate themselves this presumption is increasingly misleading. The models of excellence for libraries supporting, say, an elite comprehensive research university, a liberal arts college devoted to broad-based student learning, or an increasingly career-oriented public institution will be very different from each other.

The models of excellence for libraries supporting, say, an elite comprehensive research university, a liberal arts college .., or an increasingly career-oriented public institution will be very different from each other.

These features motivated this study. We contend that different types of academic libraries will be on different vectors, influenced by the types of universities or colleges they support. Accordingly, we set out to characterize the ways in which universities differ from each other, to develop a new way of characterizing library service areas, and then to look at how well library choices about service investments in those service areas are lining up to the type of university they are in. As we expected, we are indeed seeing important shifts.

Thinking about universities … differently

Our approach to the university typology relied on national survey data compiled by the US Department of Education in the Integrated Postsecondary Educational Data System (IPEDS), and was led by Constance Malpas and Rona Stein. We computed institutional profiles for 1500 colleges and universities, focused on two primary dimensions. The first dimension characterizes the balance of institutional attention devoted to three poles:

- research (specifically, doctoral level scholarship),

- liberal education (arts-and-sciences focused baccalaureate education),

- career preparation (professional degree and non-degree certificate programs).

The second dimension characterizes the mode of educational provision, on a continuum between residential and convenience:

- traditional residential programs are designed for full-time, on-campus students

- more flexible offerings (convenience) are designed for ‘new traditional’ students, including part-time, adult, and distance learners.

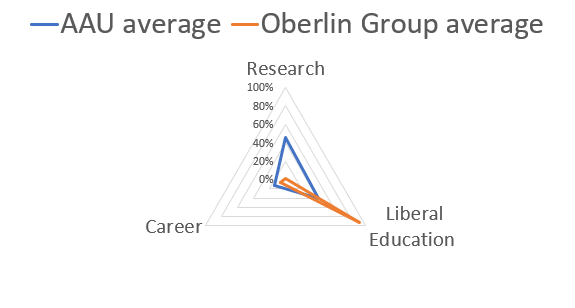

Applying this working model to a large segment of the US higher education sector makes it possible to distinguish important differences in institutional direction. A key benefit is that it allows visualization of institutional ‘types’ based on the relative emphasis of educational activity and mode of provision. Figure 1 shows an application of this kind of visualization, comparing average values for two different cohorts with distinctively different institutional profiles: members of the Oberlin Group association of liberal arts colleges, and members of the Association of American Universities, which gathers leading research universities in the US.

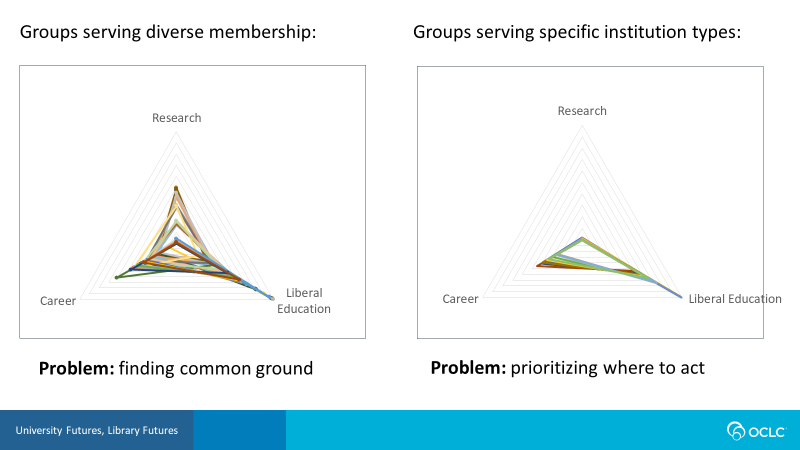

Figure 2 shows a library application. These pictures represent the parent institutions of two academic library consortia. The analysis here shows clearly how the libraries in one consortium support broadly peer institutions (on the right, where the triangles overlap), while the libraries in the other support universities with a spread of emphases (on the left, where the triangles diverge).

In a group of peers, the intersection of interests may be broad, and members may look to the consortium across a variety of activities. In this case prioritization becomes an importance consideration. Where the intersection of interests is smaller (because of size or type of institution, for example), then the common areas for consortial attention may be more limited (focused on resource sharing, for example).

Telling the academic library story differently – student success/retention, research support and community engagement

Historically, the library service was strongly associated with the collection. As the library engages more with the research and learning life of the university, so the nature of the service is shifting. The report presents a framework for thinking about library services in terms of investments in particular areas. And we explore how libraries are investing against those areas. Roger and Deanna describe our approach here.

And we do indeed observe how libraries increasingly present their services in ways that align with the main lines of university activity, which will tend to cluster around student success, research productivity and then maybe some form of community engagement. The relative emphasis will vary by type of institution.

For example, Ohio State University Libraries recently published a succinct strategic statement. The first three directions are: Equip students for lifelong success; empower knowledge creators; engage for broader impact. In this way, the library is lining up to university objectives. And if we were to judge its excellence, it would be in terms of how much it helped to make students and researchers more successful in their work. Not, in terms of collection size or gate counts. The library story is very much about how it contributes to institutional goals.

And if we were to judge its excellence, it would be in terms of how much it helped to make students and researchers more successful in their work. Not, in terms of collection size or gate counts.

Based on the patterns noted here, we can observe several trends. Academic libraries in research intensive institutions are increasingly preoccupied with support for digital research workflows and are making substantial investments in appropriate software and services, alongside continued investment in traditional, collection-centric activities. College and university libraries in institutions with a learning and teaching emphasis position themselves more explicitly as partners in instructional design and collaborative learning. Libraries in institutions that are pivoting toward more career-directed programming are creating space for career counseling services within the library, aligning library services with ‘real world’ work experience and promoting the library as a partner in preparing for life after college. These service patterns reflect strategic choices that promote increased alignment of library activity with broader institutional interests and over time, will result in a more diversified academic library landscape.

Similarly, a shift from a residential focus to more convenience-based offerings potentially calls for a different approach to library services, a more focused tailoring around course requirements or greater visibility in learning and teaching workflows.

Academic libraries are in an interesting phase of development as they engage more with the life of their institutions. We hope that this report provides useful evidence and arguments to help them plan with confidence and position with effect.

Related reading:

- Dempsey L., Malpas C. (2018) Academic Library Futures in a Diversified University System. In: Gleason N. (eds) Higher Education in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Acknowledgements

The OCLC team was Constance Malpas, Rona Stein, and Lorcan Dempsey. The Ithaka team was Deanna Marcum and Roger Schonfeld. Constance Malpas managed the project. Erin Schadt oversaw the production of the report. We are very grateful to the Andrew W Mellon Foundation for support during this project.

I would like to record a personal note of thanks to Constance Malpas for all her work on this report and for conversations which have helped shape my thinking about libraries and their futures.

Note: This blog entry draws on some of the text from this article.

Note: Slight updates on 10/21/18.

Note: Edited for appearance on transition here 29 March 2021, including feature picture and spacing.

Picture: I took the feature picture at Otterbein University, Westerville, Ohio.