I originally imagined three posts. However, as time moved on, this seemed less sensible and the material I originally envisaged will be generally incorporated elsewhere. I kept the '1' in the title for continuity of naming!

Workflow is the new content

The digital environment makes workflow support more important, as activities, content, and communications are tied together on the network in various combinations. This is especially the case as more of our activity moves to the cloud. Think of the interesting interaction of social media, computational engines, and chess, for example, or of the mix of social and functional capacities in an application like Strava, used by athletes to track and compare performance as well to connect with other athletes. In a library or research environment this trend is also clear. Think of reading and ebooks, or of the evolution of citation management applications from simple lists to fuller scholarly platforms. Research practices, and the support provided by libraries, publishers, community and disciplinary projects and others, provide an intriguing example, as workflows produce, manage and consume content, enable collaboration, and tie devices together to get things done. Increasingly, we are aware of how digital workflows are an important element of information use, and moreover how the evolution of workflow, data, and behaviors are mutually constitutive.

I have been using the phrase "workflow is the new content" in presentations for several years now. It is probably too emphatic a statement, but it has resonated.

Increasingly, we are aware of how digital workflows are an important element of information use, and moreover how the evolution of workflow, data, and behaviors are mutually constitutive.

In these posts I focus on research workflows. More particularly, I look very specifically at library support and partnership in the research process. Here are some headlines:

A complex, emergent ecosystem

Digital research practices are emergent, with multiple stakeholders, diverse service providers, and a profusion of approaches across disciplines and institutions. There is a huge range of activity in collaborative research communities, labs, universities and research centers, as well as in individual work practices. This activity is so wide-ranging, so pervasive, and of interest to so many, that it generates a rich ecosystem of communities, systems, services and data resources. This will never be enclosed by any one set of services, nor of course will it necessarily always intersect with the library.

Open: Policy and mandates

The movement to open access is complicated, with many strands. While it may have no single destination, it is a clear broad direction. Different strands create different workflow requirements (e.g. institutional repositories, compliance monitoring, managing APCs, and so on). National governments, research funders, and individual institutions are developing policies around research evaluation, open access, open science more broadly, and related issues. Some countries have research evaluation frameworks in place (e.g. the UK) which can very strongly influence research and publishing practices. Plan S represents a coalition of funding interests putting in place a policy framework for the publication of outputs from the research they fund. Depending on the context, such policy apparatus creates a need for tracking and compliance workflows. We can see how, for example, the national research evaluation frameworks in the UK have promoted early wide adoption of institutional repositories, followed by widespread adoption of research information management systems. And these in turn need to work together, and with other emerging research infrastructure. At the same time, it is clear that the industry supporting scholarly communications is evolving to adapt services and business models to retain and grow revenues in a changed environment. In parallel, a range of community and advocacy groups has emerged, variously convening stakeholders around tools, guidance and lobbying work.

Research analytics and the prestige economy: the research reputation industrial complex

Ranking and assessment have become an integral part of higher education. University rankings have become very influential and universities have become more purposeful in understanding how they work and how they might be influenced. At the same time, impact factors, citation counts, and so on, play a role in the assessment of individual researchers. Of course, this is seen by many to be distorting the research system and introducing harmful incentives, and is certainly resisted by some.

For example, as part of its move to open science, the University of Utrecht decided that it would no longer count impact factors, the h-index, and so on, in its recognition and reward frameworks. It is also interesting to see continuing extensive coverage of how well Utrecht performs in global rankings which in part also rely on that same 'research reputation industrial complex.' However, the University carefully qualifies any apparent endorsement of the rankings, noting amongst other factors that they depend too much on scoring and competition, whereas science depends on collaboration.

In this context, note the Declaration on Research Assessment, an initiative to change the basis of scholarly assessment. Three companies, especially, are heavily invested in this space. In the absence of a general industry category I call these three organizations scholarly communication service vendors. Elsevier, Clarivate [1], and Digital Science, are variably positioning themselves to support research analytics and assessment (as well as broader research workflow services, as discussed later). Each presents a graph-based view of the core of scientific knowledge as represented in the literature, through Scopus, Web of Science and Dimensions, respectively. Increasingly they want to document research entities (researchers, outputs, organizations, etc), they want to analyze research knowledge as represented by those entities, and they want to visualize research patterns and relationships. And then to provide a variety of decision support, discovery and evaluative services on top of those structures.

Market for workflow services

Given the need for workflow support, the uncertain transition to new and open publishing models, the growing market for research analytics, the need to grow and diversify revenue opportunities across campus (and elsewhere), major publishers and other organizations have been developing research workflow and analytics solutions. The evolution of Elsevier, Clarivate and Digital Science (as part of the Holtzbrinck group, also containing Springer-Nature) has been noted. These companies are diversifying their capacities through a mix of build and buy strategies. At the same time, groups looking at open and non-profit approaches have also emerged in a rich pattern of organizational models and activities (including advocacy, service and infrastructure development, training and awareness, and so on). In fact, one motivation for some of these organizations and for those that support them is to resist the role of for-profit companies in this space. Examples include the Center for Open Science, SCOSS (Sustainability Coalition for Open Science Services), OpenAIRE, and OurResearch.

Library support and partnership

Libraries are responding in different ways, individually and collaboratively. They may offer advice and referral, education and training, and may build or otherwise provide tools and services for their researchers. The library is also an expert partner for advice about evolving scholarly communication, about appropriate use of assessment and metrics, about available tools and services, and about discovering research outputs elsewhere. See this nice summary, for example, of the value the library brings to research information management discussions on campus. Support has moved beyond the original institutional repository to encompass a variety of services, which often need to work together and with other campus services. At the same time, libraries are working in variably patterned campus partnerships to provide services: social interoperability on campus is key. Increasingly, the library is positioning itself as a research partner to researchers and to research administration. Becoming involved in working with researcher workflows like this is especially important for libraries in two important ways. First, it requires cross campus discussions, establishing the library as a campus partner around research-critical activities. Second, it provides an opportunity to engage with researchers, labs, departments, and so on, in new ways, which is especially important when the pandemic has reduced interaction, and collections-based interactions may be changing. Finally, the library may be the only stakeholder that is actively interested in the long term retention and use of research outputs, a major topic in itself.

Computation and data

The computational nature of much research leads to the generation, consumption and processing of large amounts of data. This may be at individual, research group, institutional or disciplinary level. This creates a need for data management and tools support. At the same time, as the volume of publications grows, publishers and others are looking at ways of supporting computational reading at scale, mining text for insights and patterns. And finally, the automation of workflows and the generation of data of course go hand in hand, as activities are tracked and measured. The appropriate use of such tracking data is itself an important question.

Life cycles: characterizing research ecosystems

This interest in digital workflow support has resulted in many conceptualizations of the research life cycle, and mappings of tools, workflows and advice to these. These conceptualizations are important to solution providers (to characterize distinctive disciplinary workflows, for example) and to institutions implementing workflow solutions (to clarify if the right mix of solutions is on offer, or to highlight where critical service gaps exist).

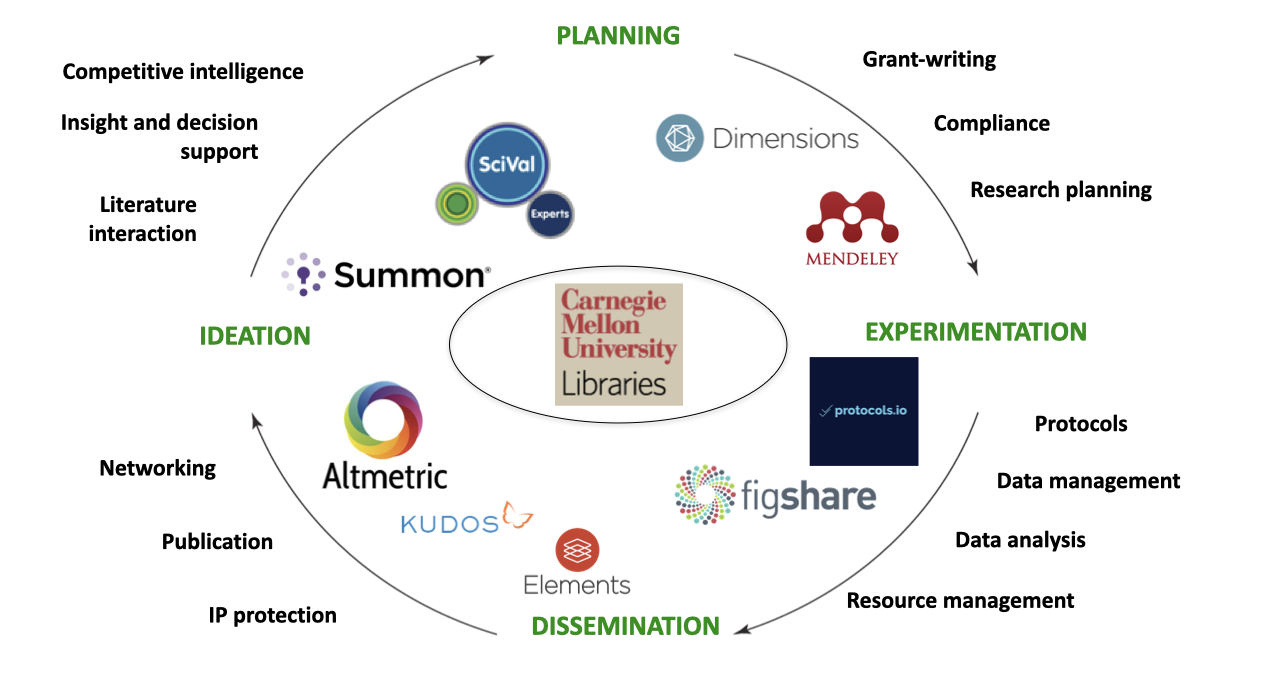

Consider, for example, this example from Carnegie Mellon University which shows how it provisions support services in different phases of a research lifecycle

This is interesting because it highlights how choices have to be made about how broadly to scope research workflow and other services, and also how to source research support services. Carnegie Mellon has a particularly extensive set of services and it is also interesting in that it has a partnership with Digital Science (which offers a suite of workflow solutions), alongside other providers. Other institutions may make different choices, prioritizing open source alternatives for example.

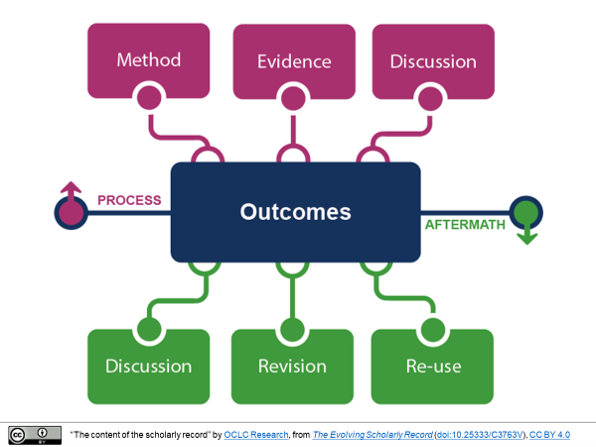

Many other examples of research lifecycle diagrams exist. The abundance of such visualizations is evidence of growing attention to workflows and how to support them. For instance, the Open Science Framework diagram describes a broad service ecosystem. It is interesting to note the variety of services mentioned, and also how many involve the discovery, management and disclosure of content of various types. The OSF schematic shows how content and workflow needs throughout the lifecycle create support opportunities for both publishers and libraries, which in turn creates more potential for both partnership and competition between these and other stakeholders.

As the Carnegie Mellon example shows, research lifecycle schematics are also helpful for describing institution-scale infrastructure. This example from the University of Central Florida depicts research workflows as a sequence of inter-related cycles, each dependent on a different mix of campus-level services. The UCF graphic emphasizes the variety of potentially involved actors on campus, underlining again the important social interoperability component of research support/engagement.

Workflows: tying people, data and applications together

As research behaviors are enacted in data-rich computational environments the way in which library support and partnership is thought of changes. Again, what is of special interest here is where workflows increasingly manage, generate and consume content. This motivates new services from libraries, publishers and a whole range of service providers and community initiatives. What are some of the areas where workflow support is important? Here are some areas where there the library is potentially a strong partner:

Curation and sharing of research outputs: the evolving scholarly record

In the print world, the final article or book was the main output. In a digital environment, the research process generates a variety of sharable research outputs: these include preprints/articles, software, research data, textual corpora, methods, and workflows. The curation and purposeful disclosure of these resources is a growing interest of researchers and research groups, universities, and libraries. It is also of interest to those who fund research and are interested in reproducibility, access, and so on. Disclosure may take several forms: on an institutional website, depositing in a local or disciplinary repository, sharing metadata with aggregators, and so on. Researchers themselves may share outputs in a variety of venues, some of which may have a discipline- or a format-specific focus. Here are some examples: Arxiv for papers in the high energy physics community, the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository for biospecimans or data sets, and myexperiments.org for workflows. General-purpose tools may also be used (e.g. GitHub for data and software). The rise of ResearchGate has been interesting in this context, building additional network value around research interests and paper sharing. And in a common pattern, there is also a non-profit initiative in Humanities Commons, built on Commons in a Box software (developed by CUNY and others, based on WordPress and other technologies). Furthermore, in some countries there is national attention to the creation and sharing of research outputs (RDNL and ARDC in The Netherlands and Australia respectively, for example, which focus on research data). Again, an important driver is national or funder imperatives to share research data, eprints, or other research outputs.

Identity and reputation management

For many researchers there is increasingly a blurring of content, workflow and network identity as they disclose and share publications and experience in Google Scholar, ResearchGate, or other scholarly communication networks as part of ongoing work. These services create additional network value. At the same time, their institutions are similarly curating and disclosing profiles through research information management systems or other systems. Visibility and impact are very important to researchers and to institutions, especially in the dynamics of the research reputation industrial complex as noted above.

Changing publishing models

The scholarly communication ecosystem is being transformed, as the pandemic accelerates research, as funders push towards open science, as new licensing models continue to evolve, and as data, methods and other outputs are published. Funder mandates or national policies may impose requirements on researchers, publishers and universities. Different open access paths may include different decision points, information needs and workflows. Universities are tracking publication for internal purposes, but now also to assure compliance with various mandates, or to track APCs or other aspects of licenses. This all creates additional requirements for managing publishing workflows.

And more

But of course there is a much broader context where workflow is important. For example ...

- Process support: Think of laboratory information systems, electronic lab notebooks, and scientific workflow systems (e.g. Taverna), which provide 'prefabricated' workflow support, articulating tools around particular processes. And at the same time, researchers assemble their own workflow from many tools - collaborative working and document sharing for instance, or data analysis and visualization approaches. The Open Science Framework, mentioned above, aims to provide an integrated platform for the management of research projects and the outputs associated with them.

- Instruments and infrastructure. Much research, especially in STEM subjects requires access to expensive or specialized scientific instruments and other infrastructure. This may again be provided in various ways, within and across institutions. Ithaka S+R recently described developments on campus with Research Cores, a response in which, typically, the Office of Research secures shared provision.

Increasingly, workflows manage, produce and consume content of interest. Later posts in this series consider some further aspects of this evolving area in more detail.

[1] Clarivate has recently purchased ProQuest. The author works for OCLC which has some products which compete with ProQuest products.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to my colleagues Rebecca Bryant, Ixchel Faniel, Brian Lavoie, Constance Malpas, and Titia van der Werf for commenting on a draft, and also to Keith Webster for his helpful observations. All interpretation and views are of course mine.

Pictures: The feature picture was taken by me in 2019 in the Taylor Family Digital Library at the University of Calgary. The CMU Libraries lifecycle picture was kindly supplied by Keith Webster.

Updates: (11 Nov 2022) Flow of opening amended. Number of parts reduced from 4 to 3. (15 May 2023) I added the label 'scholarly communication service vendors.' (15 Sept 2025) Amended to note that it was a self-standing post, and not part, as originally envisaged, of a series.